This is a guest post by Tim Adriaansen, a community, climate, and accessibility advocate.

I won’t shut up about climate breakdown, and whenever possible I try to shift the focus of a climate conversation towards solutions. But you’ll almost never hear me give more than a passing nod to electric cars. Here’s why.

Messaging an attractive future

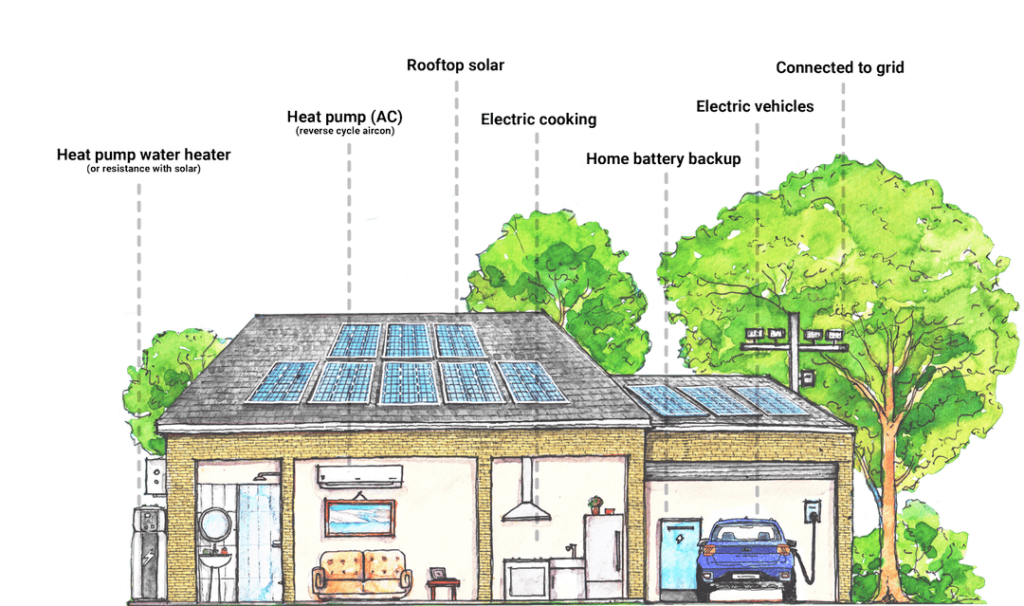

If you don’t already follow the fantastic work of Mike Casey and Rewiring Aotearoa, I suggest you head over to rewiring.nz and sign up for their newsletter (it takes some scrolling to find the signup, or follow them on LinkedIn).

Rewiring Aotearoa shows us how our lives can be made better when we shift away from fossil fuels and the damaging pollution those fuels create.

With a sales pitch for a better future, Mike Casey blends Kiwi-bloke charm with technical can-do to share a positive, refreshing and inspirational lifestyle which New Zealanders can look forward to when we electrify everything—the constructive way of saying “ditch fossil fuels”.

For those working in climate communications or advocacy, it’s a brilliant example of selling something better rather than banging on about why what we have now is bad.

This messaging is key to gaining popular support and generating the necessary political economy to move away from climate-damaging technology at scale and pace. If the audience is unaware of how their lives will be better off with what we’re selling, they’re never going to buy it.

This post, like all our work, is made possible by generous donations from our readers and fans. If you’d like to support our work, you can join our circle of supporters here, or support us on Substack!

Selling cities of abundance

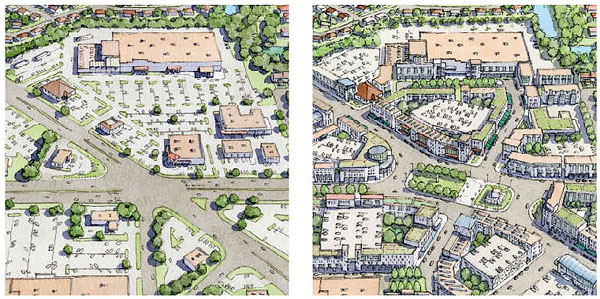

When it comes to cities, we have an unequivocal opportunity to promote a better life for everyone. More than 80% of Aotearoa’s population lives in urban areas, making our towns and cities the most attractive target for big-impact policies and systemic changes. Tackling something as broad and complicated as climate breakdown requires us to use tools as powerful and complex as towns and cities.

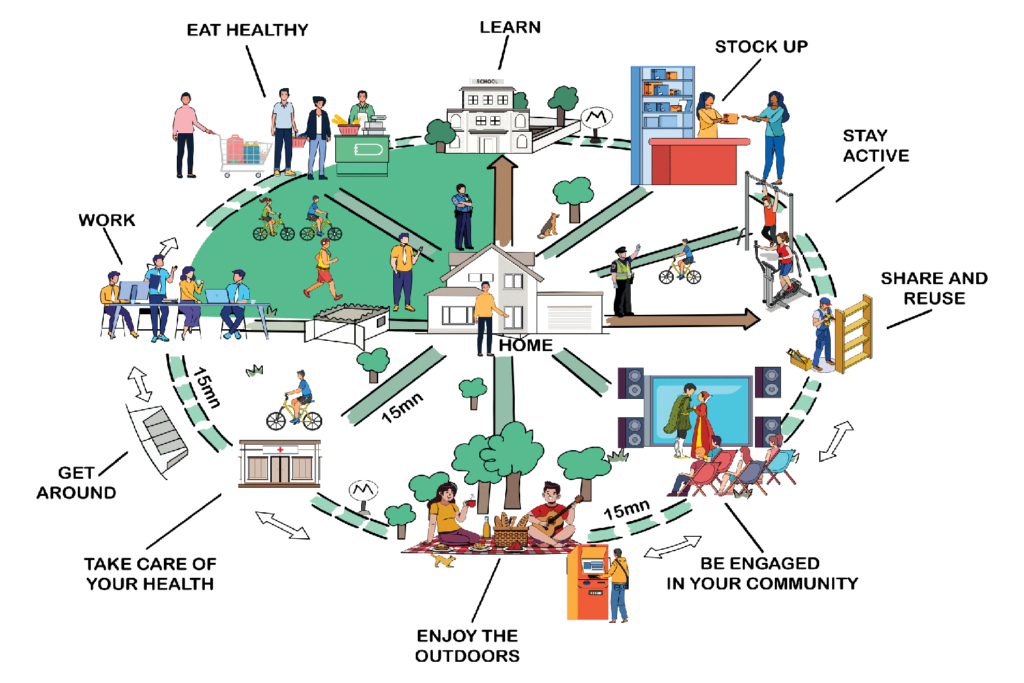

Neighbourhoods that provide suitable homes within walking distance of day-to-day needs are neighbourhoods which offer a high quality of life. They also create the conditions for low-pollution lifestyles. Per-capita emissions in dense, walkable communities are typically two to three times lower than national averages. As this recent World Economic Forum report concludes:

Achieving a better urban form is one of the most powerful things we can do for the climate – and it also means we need to build many fewer clean energy assets to reach net zero.

We will need fewer electric vehicles, solar farms, wind turbines, batteries and land (and have fewer siting and permitting battles), making the energy transition faster, easier and cheaper. This will also mean better health, greater equity and stronger economic development.

Climate-aligned urbanism offers an abundant, positive life – not scarcity – and a blueprint for a just, prosperous and irresistible urban future.

“Better urban form” means an upgrade to existing sprawling suburbs. Low-density neighbourhoods offer ample opportunity and plenty of space to shift towards walkable urban villages. We can get there by investing in shared amenities; and by enabling the construction of multi-family homes and mixed-use developments, in and around existing neighbourhood centres.

This investment pathway is significantly lower cost than attempting to connect all parts of an urban area with free-flowing roads (an approach with rapidly diminishing rates of return and little evidence of success), and caters to future growth without expanding a city’s infrastructure outwards (at further cost to current and future residents).

Shifting urban and transport planning to centre around the development of urban villages instead of expanding suburban sprawl offers a higher quality of life, at lower cost, while also reducing climate damaging pollution.

It should be an easy sell. So why isn’t it?

Finding the edge pieces

If you’ve ever solved a complex jigsaw puzzle, you’ve probably stumbled upon a few key strategies for success.

One of the most common is to seek out the edge pieces—those with a single flat side—enabling the assembly of a framework from which the remainder of the puzzle can be put into place.

When we start out, a tabletop jumble of puzzle pieces is near-impossible to decipher. But as more and more pieces fall into place, an image appears, eventually creating a captivating picture.

If we want people to see a picture of a better city, we need to put as many puzzle pieces as we can into place for them. The best way to do that is to start with the edges.

Those edges are the positive outcomes of “better urban form”.

Down one side we might have community connectedness: The social encounters that a village creates. It’s the barista at the local cafe who knows your name and how you like your coffee; the work colleague you see while riding to the office; the other parents you chat to while walking your child home from school.

Across the top edge we might have the environmental benefits: The air is cleaner and smells fresher, the streets are made greener with trees and gardens, they’re quieter and you can hear the birdsong. The way we live in an urban village helps to protect people and nature outside of our city by reducing microplastic runoff from car tyres and climate-damaging pollution from their tailpipes. In an urban village, the community can feel proud of their contribution to wider human efforts.

Another side might be the significantly reduced cost of living thanks to lower rates of vehicle ownership, less money leaving the local economy to pay for fossil fuels and a much cheaper forward infrastructure programme which focuses on local efficiency rather than regional expansion. Housing is more affordable and people spend less time commuting, allowing more time and energy for other activities.

Or it could be equity: Everybody in this picture gets an affordable home that meets their needs, be it a young family with children, a professional living alone, or a couple of older adults with limited income. They are able to get to things that make their life healthy and enjoyable regardless of their age, income or abilities. And the community is interwoven: Everybody is welcome here and supported as part of the wider team—an outcome best achieved through cosmopolitan interaction.

Finding the pieces that make up these edges and communicating them to the wider public will help assemble the picture of towns and cities that offer fantastic living—without the pollution.

One frame at a time, please

Now imagine you’re beginning to sort the pieces of a complex puzzle, putting aside those with a flat edge and making piles according to colour or pattern.

All of a sudden, somebody comes along and drops, right on top of your workspace, a thousand pieces of a different puzzle. One with similarly sized and coloured pieces, but which creates an entirely different image.

The job of creating an easily understood picture just became much more difficult.

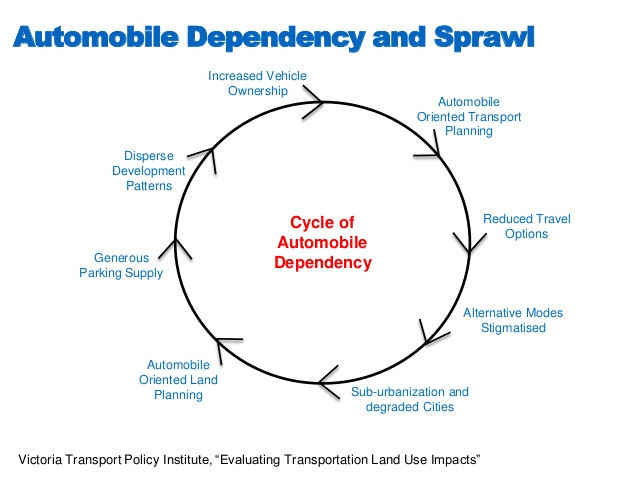

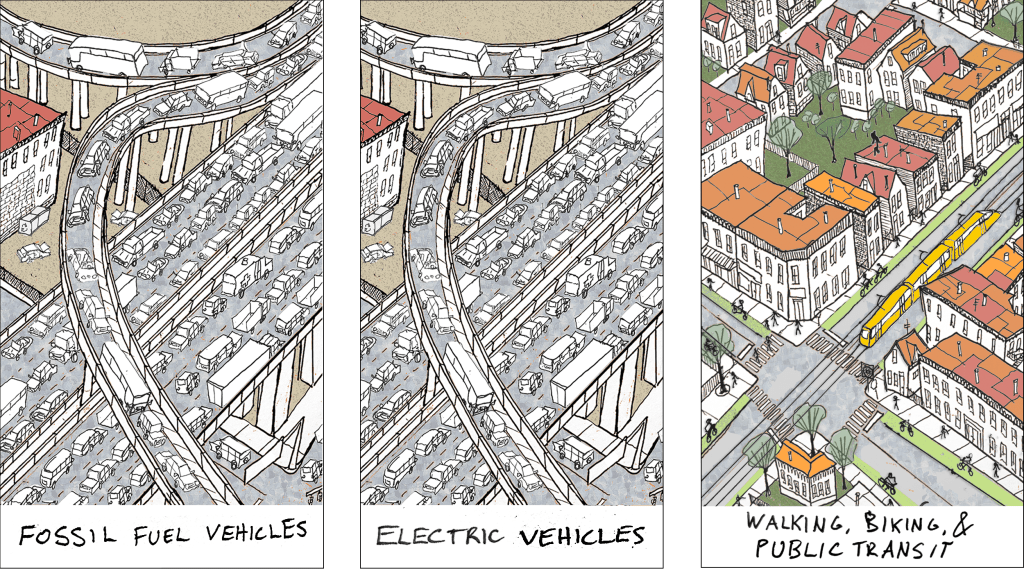

While urban villages enable abundant, joyful and connected lifestyles, they achieve a reduction in costs, resources and pollution through one key lever: Reduced car dependency.

By contrast, car-centric development inherently produces sprawling, inefficient suburbs and limits people’s imaginations around what else could be possible.

When we communicate the solutions to climate breakdown, our audience has limited bandwidth to process what they are hearing. The situation is already confusing enough—with a myriad of solutions to different environmental issues tossed in with the disinformation of sunset industries (like oil and gas companies or the automotive lobby), all competing for audience attention, emotion and action.

To the average viewer, understanding how to solve our climate challenges looks like a collection of advocates, politicians and companies threw a dozen mixed-up puzzles on top of each other hoping the audience would make sense of it all (or, in the case of some industry disinformation-spreaders, hoping the mess would be exactly as indecipherable as it is).

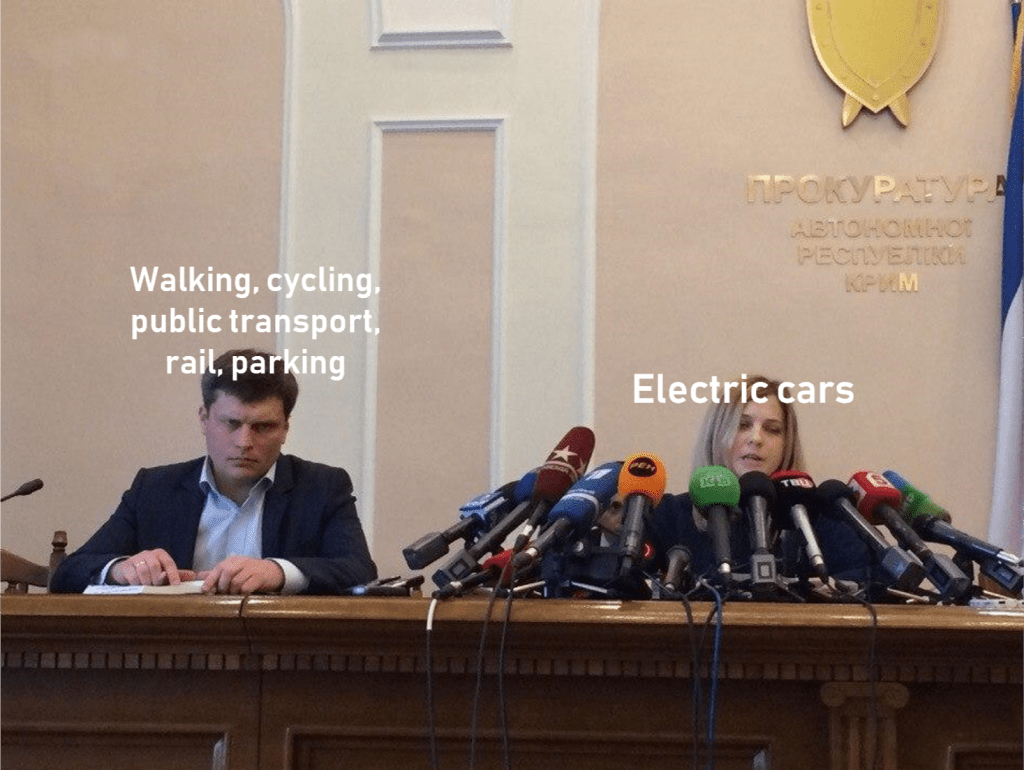

When we start assembling a puzzle with electric cars as a main feature, we inherently mess up the ability of others to create a picture where cars take a back-seat to more liveable urban environments. The two concepts compete for mental bandwidth, and end up creating a muddled pile of pieces which is more difficult for both the people working to assemble the puzzle, and the people who we hope will interpret it.

Electric cars cannot solve (and sometimes make worse) problems with safety, affordability and fairness. They cannot resolve transport or access issues created by car dependency—like congestion, isolation, physical inactivity and transport poverty. Even when electrified, cars are highly polluting and resource-intensive. To resolve these issues, we must illustrate a better way to live in our towns and cities.

The good news is that electric cars are an important part of a thriving urban environment, so we don’t need to cut them out completely. If we look at the picture of an urban village, we’ll see a variety of electric vehicles ready to be put to use to meet the community’s needs. And much as Rewiring Aotearoa promotes, they’ll be charged with renewable energy and support a balanced local electrical grid. The cars are there, but they’re not what the picture is about.

For advocates and climate communicators, it’s critical that we don’t mess up each other’s work by putting electric cars front-and-centre when the big picture frame we need to create is one of fewer cars, not newer cars.

Processing...

Processing...

Spot on – in our jigsaw we have just had gas removed – we already have solar. The plumber said he was getting more and more requests to remove gas ( great) but did also mention the new developments going in with gas – does make me wonder why a council that talks about climate change consents large developments tied to gas.

We moved into a new town house a few years ago which we brought when still had scaffolding up and near completion. It came with gas but we asked for PV solar panels + induction hob instead. The developer was surprised as apparently most buyer don’t ask; and took down scaffolding before we could arrange PV panels.

My suggestion several years ago was to leverage the same idea of a relatively cost neutral feebate scheme like for EV’s.

So a modest fee like $1 – $2k on cost of any new builds completed with gas appliances. That fee used to provide a rebate on new builds with PV and pure electric appliances.

Would have to reduce emissions a little, but of course this government seem hell bent on increasing emissions, so not going to happen any time soon.

There is no need to put any fees on gas. Anyone replacing an appliance with a gas one is dumb, as gas prices are about to skyrocket.

Our gas fields are running out and underperforming and there isn’t a lot of likelihood that’ll improve. We can import from overseas but that won’t be cheap. But the biggest bill coming down is the gas network charges – which are going to go nuts for a few reasons.

Firstly, under maintenance and that bill is coming due. 2nd, higher cost to maintain with inflation. 3rd, less users to split the gas costs over.

They’re already looking at closing parts of the network (as maintenance is more expensive than just telling them to get cylinders delivered).

Solar and electric appliances stack up already by themselves, and they’re getting cheaper. Gas doesn’t stack up, and it’s getting more expensive.

Plenty of info on this:

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/piped-gas-network-heading-for-death-spiral-when-prices-rise-report-warns/C7X4XEI2OFGZTBDXFWPBG4HDQA/

A nicely written piece. But how to get the affordable homes you talk of in these compact, walkable communities? The private sector won’t deliver them.

A key part of the answer must surely be much larger funding of the community housing sector so we see much more shared equity housing options delivered.

The private sector won’t deliver what’s not profitable.

What we need the council/govt to do is create the sandbox, create the rules so the private sector can deliver what they want.

It’s perfectly ok for someone to want a single family home and a driveway, same as it is someone wanting a few tiny homes on similar size piece of land in the same area.

Relax zoning rules.

Relaxing zoning rules only gets you so far. In itself, necessary but not sufficient.

I think my clients make it illegal for me to recommend rates / development contribution changes that make infill / urban development more financially attractive than greenfield development. So the libertarian approach of liberalising zoning alone must be true 😉

[Joking, of course. NZ’s libertarians are in fact headed by someone who advocated for more restrictive zoning, especially on freedom-destroying abominations like apartments!]

Zen Man you’re on right track

Average Aucklander get out the YIMBY pipeline before you become like The Bish

the environmental benefits of electric vehicles tend to be exaggerated. As many have noted, although they are referred to as “zero emission vehicles,” they are really “remote emission vehicles.” In France, with its heavy reliance on nuclear power, their use reduces greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 77%, still a far cry from zero. And the heavy sales numbers in China reduces the overall savings, since two-thirds of China’s electricity comes from coal power, reducing the emission savings by about half.

The difference from zero and actual emissions is the result of the energy-intensive manufacture of the batteries (and other materials in the vehicle). Since China produces the majority of the world’s lithium-ion batteries and again, is heavily reliant on coal for power, the emissions reductions are that much less., And, how do I dispose of the battery from my electric car, when it stops charging in about four years time

I’m not going to bother responding to the whole of your rant, only the last part: how do I dispose of the battery from my electric car, when it stops charging in about four years time

Mate, there’s 2nd hand Leafs on the road. They came out 14 years ago. In the US there was at least one Tesla with a million miles on the clock on the original battery.

Actually, I can’t resist the temptation – MIT disagrees with your energy rant. https://climate.mit.edu/ask-mit/are-electric-vehicles-definitely-better-climate-gas-powered-cars

From the article:

Building the 80 kWh lithium-ion battery found in a Tesla Model 3 creates between 2.5 and 16 metric tons of CO2 (exactly how much depends greatly on what energy source is used to do the heating).

The researchers found that, on average, gasoline cars emit more than 350 grams of CO2 per mile driven over their lifetimes. The hybrid and plug-in hybrid versions, meanwhile, scored at around 260 grams per mile of carbon dioxide, while the fully battery-electric vehicle created just 200 grams.

Please keep your comments civil.

Although many fully electric vehicles (EVs) carry “zero emissions” badges, this claim is not quite true. Battery-electric cars may not emit greenhouse gases from their tailpipes, but some emissions are created in the process of building and charging the vehicles.

One source of EV emissions is the creation of their large lithium-ion batteries. The use of minerals including lithium, cobalt, and nickel, which are crucial for modern EV batteries, requires using fossil fuels to mine those materials and heat them to high temperatures. As a result, building the 80 kWh lithium-ion battery found in a Tesla Model 3 creates between 2.5 and 16 metric tons of CO2 (exactly how much depends greatly on what energy source is used to do the heating). This intensive battery manufacturing means that building a new EV can produce around 80% more emissions than building a comparable gas-powered car..

https://climate.mit.edu/ask-mit/are-electric-vehicles-definitely-better-climate-gas-powered-cars

You don’t have to dispose of the battery. You just drive the car until the battery combusts itself.

Always carry marshmallows in your electric vehicle.

You are commenting on an Auckland blog site with total nonsense using examples of energy consumption from France and China?

I would give you NZ figures, but don’t believe your comments are made in good faith, so pointless trying to correct you unless you prepared to be reasonable and learn. Lots of misinformation, but classic denier tactic to talk about the ~300kg battery in an EV (much of which is aluminum) which is part of a 1500kg – 2000kg car, and some how overlook that every year an ICE is on the road, you have to pour ~1000kg of fossil fuel into it, turning that into pollution, emissions, heat, noise and modest amount of motion

For the record, my wife’s Leaf was made in Japan, is now 7 years old and still going strong despite the Leaf’s famously poor battery life. It is charged from a grid that is mostly generated by renewables, and a grid that can (and will), get cleaner over time now that wind/solar are cheaper than coal (and our last remaining coal plant is approaching end-of-life)

EV’s are not perfect; and yes, walking, cycling and using PT are better, but we needed a car for my wife to get to work, and quite simply, the EV was the better choice for us and for the environment.

That was us. Needed a car either way, might as well be an EV. Don’t think I’d ever buy a petrol car again unless it was a collectible or classic, at which stage they take on more of an artistic or architectural value than a mode of transport.

No you can’t drive a Picasso to work, but it shouldn’t stop us from appreciating a classic hero car of its day in the same way.

Heads up Tim,

Massive RORO ferry loads of cheap awesome zippy cute eCars are going to be delivered in huge quantities from China. BYD Seagull and similar for NZ$15K are going to clog up our arterials/arteries like never before, and power our houses with V2G and other easily justifiable capabilities.

All you say is correct, but the RORO’s are on their way and the Chinese megafactories are cranking up.

Rewire.nz totally, but today’s hydrogen policy seems very far from that high mobility vision.

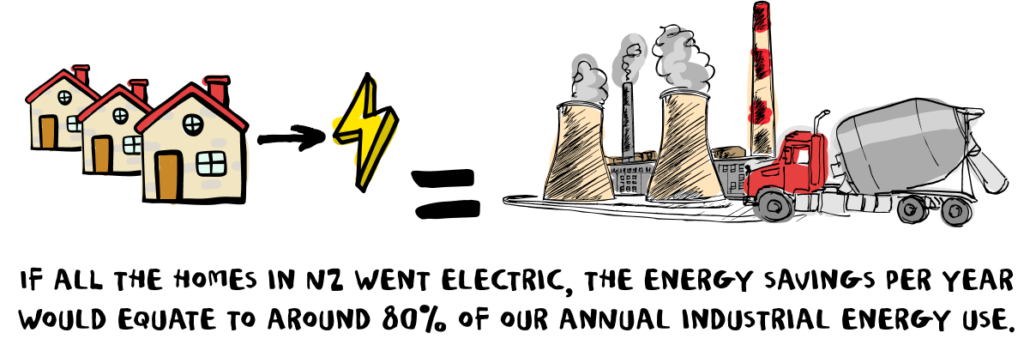

Well said, Tim. We need to win on many fronts and the EV is possibly last for owners of existing homes. Provided you aren’t about to launch into the community rebuild advocated above AND think your home will be around for more than a decade it is worth; adding solar PV to the roof, converting to electric hot water, electric cooking and electric heating and cooling.

Each of those project is a $5 to $15k excerise depending on a variety of factors, say $20 to $60k all up for which you can get a 1% green loan from many banks. As well as saving your household running costs these projects will ADD VALUE to your home and insulate you somewhat from price gouging gentailers.

Once this is all done think about adding your own battery or subscribing to the community battery service which will be coming shortly to a neighbourhood near you.

FINALLY, think about the EV because by then you may also have moved to Public Transport or an e-bike or both.

This is where I agree with TIm – do the car last.

The car can also function as the solar battery. Leave it plugged in during the day ( and overnight) whilst you use PT to get to work. Use the car for the things where PT won’t work. Essentially think of the car as part of your solar system that can be used occasionally as transport.

Really well put. I’ve always thought that the reason EVs are being adopted by the professional managerial class so quickly is that they represent the status quo. If our vehicle fleet went 100% electric by 2030, what would really change? Still the same (if not more) roads and highways, the same car dealerships & advertisements, and largely the same industries feeding into (and off of) the transport system. EVs still represent individualised movements and ultimately a consumerist response to our current situation.

Even renewable energy is a little misleading, for this power is still coming from an exploitation of nature and resources.

With a 100% electric vehicle fleet there would be no petrol stations, transporting of fuel etc. The auto parts industry would be greatly reduced as would the servicing industry. I recall comment that half of world shipping is moving oil and its distillates to end that would have significant emission reductions.

Hi teacher, it’s great to hear you are concerned to reduce resource waste.

Consider this: The import of fuel oils require around 20 visits to NZ by long range oil tankers EVERY YEAR.

Versus 20 and 40 container ship visits that would be required ONCE to deliver enough solar panels for EVERY house in NZ.

A fair percentage of that solar juice would substitute for the fossil juice and reduce the waste associated with shipping it around. Relacing local generation with imported fuels will reduce waste.

“Buying a Tesla is perceived as trendy,”

And now also perceived as supporting a fascist narcissist!

Should have gone under the next post below…

I believe that the so called ‘professional managerial class’ will lead the way on changes when suitable substitutes are found. They are educated, understand the problem, so they will jump at an opportunity to do their part when a substitute exists. But they are not ready to change for a ‘lesser’ product.

And thats why talking about solutions matters. Most non hardcore climate activists do not want to change their lifestyle, hence providing substitutes is key. Tesla did, they are a market disruptor and they provided an excellent substitute.

Buying a Tesla is perceived as trendy, its perceived as cheaper to operate and its also perceived as helping the environment. It speaks to our vanity, our wallet and our hearts and thats why its such a roaring success.

Next step is our power generation. Its not ideal if we manage half of New Zealand to trade in their combustion engines for battery powered ones and then charge those vehicles with ‘dirty’ electricity from Huntly…

we know need the support for solar that they have in some Australian states. And not just for residential buildings, the real low hanging fruits are the malls, and the large corporate buildings.

For example, Sydney is building a new airport, its roof is covered in solar and so are the covered walkways, garages etc etc. Compare that with all the newbuiklds we have seen at Auckland Airport. Imagine if the garage, the new terminals, walkways and hotels at Auckland Airport would have done the same (I know there are some panels, but its far from covered like the new Sydney Airport).

One aspect of Electric vehicles not explored here: Noise. Petrol-driven cars, trucks, and motorbikes are just so damn noisy. Some more than others. Enormous shuddering waves of sound spewing out of Kenworths and ICE buses, along with eardrum shattering farts from Harleys and tiny 50cc wasps – the one thing that I really hate about city living id the incessant noise from inconsiderate others. And the worst of them, by far, is the impotent roar of a dickish boy racer on a motorbike or someone trying to show off to another dick in his car. For heaven’s sake, grow up and turn your sound down!

I live on the same block where FTN Motion used to build their electric motorbikes – and nothing is more beautiful than watching a Streetdog roll by, sans sounds, making the world a better place. Spooky, but enjoyable in the extreme. Roll on the day when all vehicles are electric I say – the best car is one in which they could be seen but not heard.

+10

Over a certain speed electric cars aren’t much quieter than ICE ones. Slow moving vehicles in central city will be a little quieter. Fast moving on the motorway the roar will remain as it not just generated from engine noise.

Yes. The urban village model is so much quieter, regardless of how the cars are powered.

A major attitude issue is “What is good for all of us,” versus “What is good for me.” How do you think about our city? If government keeps worrying about how a lot of ‘me’ thinkers are likely to vote, democracy doesn’t have a chance, nor society, iwi or however you describe the community.

Solutions for all of us are important, so the solutions for ‘me need to be framed as those that are good for all.

I find this post frustrating in that at a household level 94% of our emissions are from transport. So pretty much everything else is just noise. So featuring rewiring Aoetearoas mantra of solar panels everywhere is just wrong. As the previous parliamentary commissioner for the environment said if you want to do something meaningful about climate change, putting PVs on your roof in NZs unique situation is a poor choice – it is much better to get an electric car. What she was really saying is that with our electricity system already highly renewable (97% right now), with winter evening and winter early mornings being our peak in electricity demand, being diametrically opposed to peak summer daytime solar generation, domestic solar electricity a poor option – better to go for zero carbon transport. And for many people an electric car has to be part of that: expecting everyone or even most people to never use a car is unrealistic as we transition to denser built environments.

“is unrealistic as we transition to denser built environments.”

Huh? It becomes *more* realistic as we transition to more density. And I don’t see this blog as talking about “expecting most people to never use a car”. It’s talking about how electric cars are used as a fig leaf to not have to change the general approach on transport and our status quo – “See, we are doing stuff! (while not doing much)”.

Peter, there is no conflict. We can nod in appreciation of the family that chooses an electric vehicle for their situation while supporting the urban village model Tim writes about.

The point is that from a public policy point of view, changing planning roles and changing transport investment plans to support dense walkable (etc) neighbourhoods is game changing. Whereas a vision of a transport system that is like today’s, but electric, is a failure.

It’s an easier sell because it doesn’t require nearly as much systems change, but it’s not going to deliver the safe, accessible, low carbon, quiet, healthy cities that we need and deserve.

I see this as a huge flaw in logic. We need to do everything in parallel, because our current state is adding more pollution every day.

We should move away from coal, and move towards solar and wind.

We should move away from ICE vehicles and towards EVs.

We should move away from single-mode systems and towards multimodality.

It’s pointless to engage in purity contents and fringe infighting when there’s so much work to be done.

Logan, you’re absolutely right and most people just haven’t the band width to do everything, all at once. My wife and I are confident early adopters and happy to navigate our way through the shoals and currents of ambiguous change. In talking to others about our journey it is obvious the “disinformation of sunset industries” has done a wonderful job of seeding doubt, caution and downright angst amongst so many.

On our second electric car. Love it.

I just love driving. Even more with the smooth sweet power of the electric.

I don’t want to walk. I want to drive.

Your anti car stance is mean spirited.

I just plainly love to drive the electric. Walk if you will, I’ll drive!

The perfect lifestyle might be living in an apartment (of an appropriate size) with ample access to amenities including the natural spaces that are relatively abundant in Tamaki Makaurau.

Being an anti car person for a couple of decades, I have survived bigger, and smaller places than this city, in varying extreme weather conditions, and found the lack of a car to be not only less costly, but also less dangerous.

The Electric Vehicle defeats the purpose of reversing the damage that motorway syndrome has done to our planet, and is simply a way to keep us all isolated from one another, in a slightly less smelly metallic bubble.

Public Transit is the most effective way of moving people, as our CRL will prove, but it is sad that we cannot be progressing with other heavy and light rail projects, which would complement the CRL.

Wasting time, and money, on infrastructure designed for private motor vehicles, will only send us back to the past, and faster towards the desolate future that waits us on the other side of climate change.

A certain generation would have grown up with 2001: A Space Odyssey, and another with the Terminator, two future worlds that we should do everything to avoid.

The machines will destroy us when they can, and in the meantime we seem intent on destroying ourselves.

Ride a bike, even in the rain, splashing through puddles is rather fun, especially if you are stuck in the adult world of pretending to be grown up.

bah humbug

This post has broken so many commenters brains, we’re voices of reason today and I sometimes agree with you and Unlearning Economics that we should… BAN CARS!!!!

“The air is cleaner and smells fresher, the streets are made greener with trees and gardens, they’re quieter and you can hear the birdsong”

That’s the case already in most New Zealand towns, and also in the outer suburbs of the larger cities. Ever lived in Waitakere or Titirangi?

I think you’re missing the obvious – relocate yourself!

Small town NZ has always been, and will always be, better. The only people who benefit from density are developers.

Small town NZ presents opportunities for the re-creation of low carbon, safe and accessible villages, but we are most certainly not there. Typically, the passage of huge trucks is prioritised over safe walking and cycling. Excessive parking combined with lower congestion means distances that could be easily walked are typically driven. Kids biking around are not safe. Vehicle km travelled per person is high.

Yes large trucks roll through small towns because a particular group of people fights any money being spent on much much safer bypasses. See the irony you can’t claim you care about safety while continuously fighting any effort to make a safer route for these trucks to bypass. Just admit you are purely fighting these bypasses in the interest of being anti car and focus energy into improving Auckland’s PT because spoiler alert PT will never work in small towns it’s not worth doing except for maybe the school bus.

If we all moved to small towns they won’t be small any more.

Sure, moving from ICE vehicles to electric vehicles, will mitigate one of the problems of our dependence on private transport for mobility.

But it does nothing to address the other very significant issues.

Nearly 2 tonne vehicles hurtling through our streets at fatal impact speeds, minimally separated from pedestrians, and other more spacially efficient transport modes, as these others perform such necessary, but mundane tasks such as merely crossing the road.

And nothing to reduce particulate pollution from tyres and roading surfaces .

And nothing to reduce the incredible drag on the economy by using precious land for such low value activity of storing all these machines, especially during the premium commerce hours, in, or close by, the highest valued commercial land.

We need to concentrate on land use development, or most likely redevelopment, that reduces both the number and distance of private motor vehicle trips.

Electrically powered or not.

And of providing safer and more spacially efficient means of accomplishing these trips.

So intensification, and more public transport provision.

Concentrating on electrifying our vehicle fleet is just making what we are doing now, slightly more sustainable, when it is how we are presently catering for transport needs is fundamentally unsustainable.

There are plenty of examples overseas, and now even in Auckland, how this can be achieved. But it does disrupt the income streams of vested interests.

Interests that are much better served by merely replacing ICE vehicles wit new electric ones.

Excellent post, Tim. Thanks

The Greedy Green Party has just announced an alternative to having heavy vehicles and Uber Eats delivery vehicles from using the roads in New Zealand

They propose to start running Govt funded training schemes to start building these: