This is a guest post by Ed Clayton and Stu Farrant. It’s based on a talk delivered at the recent Transportation Group Conference in Nelson.

The water street renders are by Tom Greer. Ed notes: “Tom is a freelance landscape architect with a background in ecology and environmental science. Hit him up for some work!”

URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND OUR HISTORY WITH WATER

The role of water in shaping the places we live cannot be overstated. As a dynamic and geologically young landmass the influence of water over millennia is clear to see across Aotearoa New Zealand. As tectonic uplift raised our central ranges, the power of water eroded them down to create a landscape intersected by waterways which have deposited vast amounts of sediments to create coastal plains, estuaries and a variable landscape of freshwater wetlands, lowland forests, and waterways at all scales.

It is this landscape that informed and guided initial development and movements, with early Māori explorers quickly recognising the importance of living alongside these natural features. As sources of food and materials (mahinga kai), providing natural barriers to invaders and useful pathways between coastal settlements and inland hunting grounds, water provided a wealth of resources and benefits.

The European colonisation throughout the 1800’s brought a similar linkage with water, albeit on the different scale. Initially seeking safe anchorage and protected harbours, many coastal estuaries were favoured for early colonial settlement. This often brought conflict with the resident Māori inhabitants who had long established Pā, kāinga and mara in these same locales.

Where streams and wetlands were not filled in or drained, they were used as open drains to convey human and commercial waste away from the growing towns and cities. The original Māori pathways (which often followed waterways) were gradually expanded as they progressed from walking paths to bridle tracks, bullock cart tracks and eventually roads to support the rapid ‘development’ of inland areas.

URBAN STREAM SYNDROME

Regardless of whether streams are currently within pipes or flow openly, where they flow through urban and developed areas they are subject to a range of acute and chronic impacts as a direct result of urbanisation. Modified flow characteristics, discharge of urban contaminants and changes in the physical characteristics of the water combine to adversely impact on the health of these streams and the ability of them to support functioning ecosystems. Further, instability and persistent discharge of flashy flow in even small to moderate rainfall events cause ongoing undermining of public and private infrastructure resulting in often expensive (and impactful) to fix.

This results in “Urban Stream Syndrome”, where paved areas create faster runoff, leading to streams that have higher flood peaks and more erosive power, transport more pollutants and sediment and have fewer species and less complex ecosystems. In turn, we have experienced a declining connection between communities and the waterways which define the catchments in which they live, work or travel through. Where streams have historically been piped, the urban stream syndrome is further compounded by the lack of any visual connection with waterways and in many instances a lack of awareness of the presence of waterways and the role they once played in defining the landscape and the ecosystem services that attracted people to the catchment all those years ago.

But when it rains these long-neglected streams rear their heads and make their presence felt at the surface of our urban centres. Due to limited capacity of underground piped networks, development within overland flow paths and infilling of flood plains, these waterways re-engage the water landscape and again flow across our now highly modified landscape. Where once the presence of riparian/flood plain forests and deep, rich soils slowed down and adsorbed rainfall, the now increasingly impervious landcover results in increased volumes and flowrates of floodwaters. These are increasingly concentrated through restricted overland flow paths which are often aligned or intersected by road corridors.

MITIGATING ROAD WATER QUALITY ISSUES

Mitigating the effects of road runoff has long dealt with altering the energy characteristics of stormwater in order to reduce the energy available for transporting pollutants or eroding stream channels. This results in such features as vegetated swales, rain gardens and constructed wetlands designed to filter and detain runoff, additionally allowing adsorption of contaminants and removal of sediments.

The effectiveness of these devices varies with different reported factors of load or concentration reduction dependent on catchment, location, device and climate circumstances. However effective they may be, these industry-accepted solutions do nothing to change the underlying cause of road-derived pollution or water volumes – the transport activity and infrastructure materials themselves. (For more information on water pollution, see my other articles on GA, here, here and here).

A STREETSCAPE THAT MAKES SPACE FOR WATER

The concept of “making space for water” is increasingly being promoted across Aotearoa and internationally and specifically by Auckland Council’s Healthy Waters department following the damaging floods of early 2023. The concept recognises that flooding is both natural and expected to increase with future climate change and that there is therefore a need to ensure that communities are safe from potential harm and to minimise financial costs from damage to property and infrastructure. In part, it aims to increase resilience to flooding by creating blue and green networks through cities so that stormwater can safely move through the city, and to manage overland flow paths.

This often encompasses existing open stream corridors and adjacent green spaces (such as sports fields) and from an engineering sense there is a tendency to look at achieving this through further modifying remnant streams to increase the available cross sections and manage the channels as flood conveyance ‘drains’. This approach further degrades the ecological integrity of remnant streams and waterways and is counter to aspirations to enhance urban ecology and re-connect communities with natural freshwater environments.

Conspicuously absent from discussion has been the potential to appropriate the public streetscape to contribute to stormwater management. Mode share of transport is still dominated by private vehicle use, prioritizing individual transport needs rather than the best use of public space. With the knowledge that our streets have followed and built over streams in the past, here we explore how we could reimagine our streets to make space for water. Making space for water requires us to examine the value that we place on stormwater. Rather than a nuisance, to be piped and conveyed “away” as fast as possible, what if our urban spaces could claim stormwater as a resource and amenity?

One of the common challenges with the management of stormwater for ecological or socio-cultural values is the misalignment with requirements legislated under the land transport act. This act is quite rightly intended to manage the safe and resilience of land transport infrastructure and its users but unintentionally is often an impediment to configuring and operating road corridors to support multiple benefits.

This typically results in road corridors (and associated stormwater infrastructure) being designed, implemented and operated by separate arms of councils and except for regulated requirements for water quality (where mandated) and passage of existing overland flow paths they are not designed holistically with the wider catchment in mind.

The concept of ‘roads as a catchment’ reflects the fact that typically roads are characterised by extensive areas of impervious landcover within were what once natural stream catchments. This contributes to an increased volume of stormwater, particularly during small to moderate rainfall events which is often referred to as an “urban excess”.

Given the need to capture and treat this stormwater to mitigate water quality impacts and the importance of retaining a portion of this increased volume, there are clear opportunities to divert treated stormwater to nearby and adjacent demands for non-potable water. This can include large scale irrigation demands (such as sport fields, plant nurseries, community orchards or high amenity landscapes) or appropriate commercial users (such as water tanker refill, washdown or process water for suitable manufacturing activities).

COPENHAGEN

Following damaging urban flooding in Copenhagen in 2011, the municipality, stormwater managers and urban planners looked at the levers and barriers to providing more space for water within a highly constrained urban environment. This identified that existing road corridors were ideally located to collect, attenuate and convey stormwater but that these are largely managed solely for the transport function for which they were originally designed.

To rectify this, changes were made to the national legislation to enable these road corridors to be managed for stormwater (as well as transport) and therefore enabling stormwater planners to consider projects to lower the surface levels and where appropriate intentionally increase the depth and extent of inundation within road corridors. This is seen in the “cloudburst” retention boulevard profile, but is also supported by redesigning the smaller adjacent streets to slow the movement of water before it reaches these flow paths.

GOTHENBURG

This approach has also been manifested in Gothenburg, Sweden, where the fact that it rains on average every three days has been claimed by city officials to create a “Regnlekplatsen (Rain Playground)”. Playgrounds are designed to retain rainwater as puddles for jumping in, with sheltered benches and tables. The winning design for a new school features a schoolyard that changes when it rains, with waterfalls, a canal and a marshland with real mud.

NORTH AMERICA

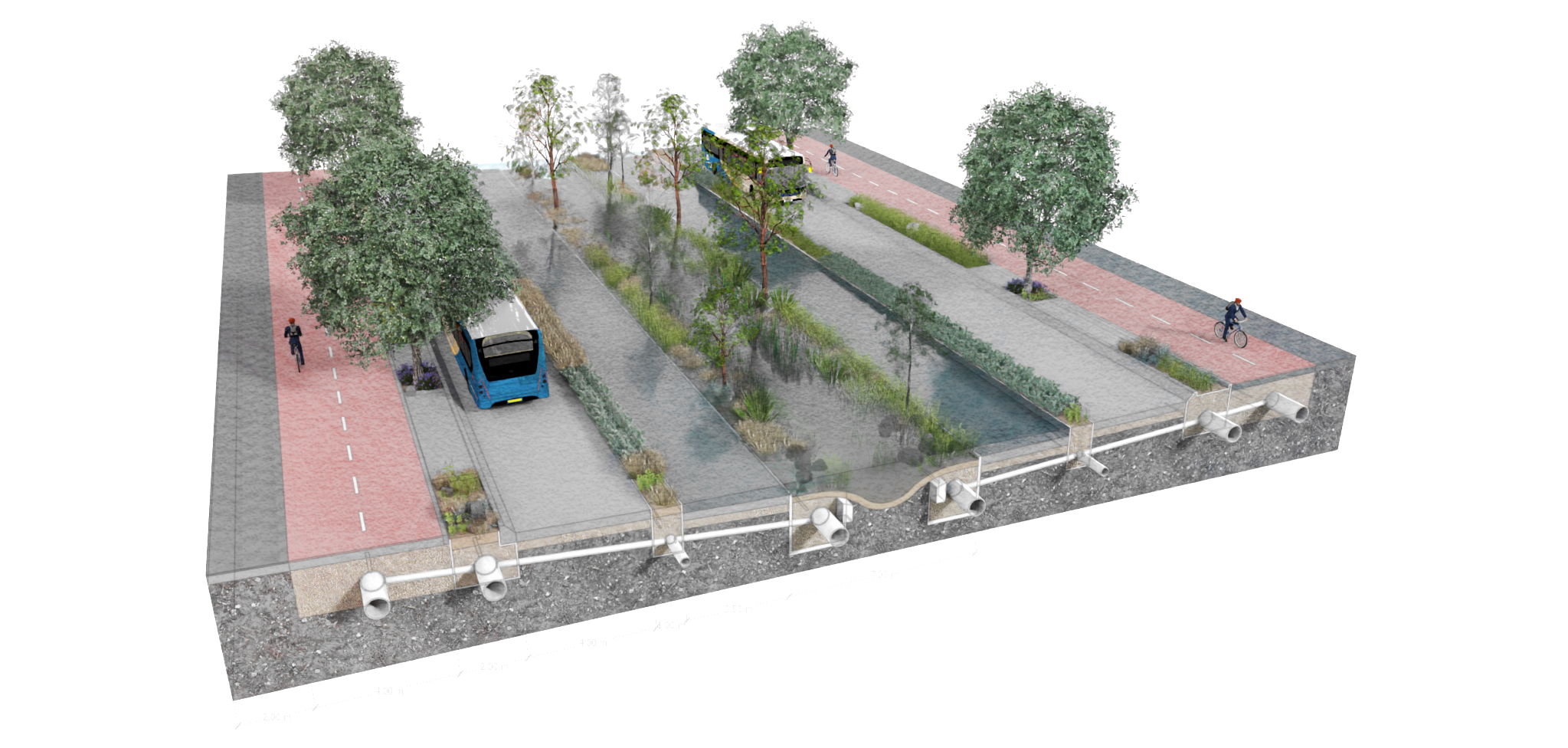

“stormwater greenway” in North America. The centre of the street features a daylighted channel, trees are planted to intercept rainfall and raingardens provide biofiltration functions. The reduction of car traffic reduces pollutant generation and bike paths are installed with permeable surfaces to promote infiltration. Pedestrian areas are elevated so that surface flooding affects these spaces last, this can be achieved with a cross section utilising an inverted crown so that all surface water flows towards the centre of the street (and hence the daylighted channel).

AUDACIOUS ENGINEERING?

In some instances, there is a tendency to jump to the large and audacious end point with aspirations for things like stream daylighting like happened for Cheonggyecheon in Seoul. As community awareness of these piped awa becomes more widespread, and increasing mana whenua calls for uplifting the Mauri of the awa, the temptation to visualise what could be is strong.

These daylighting projects create beautiful streets, but often require large scale engineering works that can make these aspirational ideas easy fodder for disparaging engineers who can use the inherent challenges as a reason to do nothing instead. (Full disclosure, I love these aesthetics and want daylighted streams with green light rail everywhere!)

A LONG TERM VISION

Creating Water Streets doesn’t have to be an immediate, all-encompassing project. It is important to understand the challenges with the very real constraints such as highly degraded water quality, clashes with a myriad of underground services and ‘forced’ invert levels due to historic piping.

There is a strong need to first establish a clear vision of what is wanted in the long term and then clearly communicate the longer-term trajectory to achieve this.

Before we achieve full stream daylighting as envisaged above, we may need more integrated solutions where baseflows are diverted to smaller scale surface recreated waterways integrated with the public realm. Existing pipes remain in the ground to pass the more contaminated ‘first flush’ and infrequent large scale flood flows are accommodated within the wider road corridor with event triggered restrictions on the use of some or all carriageway during large scale storms, priority being given to passage of public transport, emergency vehicles and pedestrians/active transport.

The greater the intensity of rainfall and severity of the flood, the more of the cross section can be used to convey water. Signalised pedestrian crossings can recognise when it rains and increase the frequency at which pedestrian priorities are called, reducing the time that people wait in the rain. Cycle lanes with permeable paving can provide an infiltration buffer and would be built wide enough to accommodate emergency vehicles.

A hypothetical Water Street within the Kent and Cambridge Terrace corridor, showing different inundation profiles from baseflow (first image) through to full flow (final image). Renders from Tom Greer

Such an approach would also achieve objectives of the Aotearoa Urban Street Planning and Design Guide. This actively encourages street designs that work towards living environments that provide the unique context and value of their location.

Our approach of streets that make space for water directly aligns with the document’s recognition that streets are public space and multidimensional, and that we need to realise that streets are ecosystems. One lever that could be applied to facilitate these adaptations would be for local authorities to recognize and plan for water streets in district plans.

These changes will necessitate a change in mindset – where communities collectively recognise that private vehicle travel will be less convenient during extreme rainfall, but that this contributes to reduced adverse impacts on private and public property and enables cities to be more resilient and able to return to ‘normal’ sooner. In turn, recognition of the increased resilience is reflected in reduced insurance premiums.

REALISING FURTHER BENEFITS

Put together, these approaches provide further intangible benefits. Increasing urban blue-and-green-space is known to improve people’s wellbeing, even if it is only experienced through passive observation.

Provision of street trees and native vegetation in nature-based stormwater devices such as raingardens, swales and floodable pocket wetland parks can encourage wildlife back into urban areas, allowing streets to function as ecological corridors. Increased pervious surfaces allows more water to seep back into groundwater, recharging local aquifers and providing more consistent stream baseflows and better aquatic habitats.

To summarise, integral to this approach will be the improvement of our connections with urban freshwater, visually, socially and culturally. Such an approach presents multiple benefits but will be challenging, requiring a shift in the way we place value in stormwater from nuisance to resource.

If we wanted to extend the management of stormwater further than just the streetscape we could then look to implement catchment-scale Ecological Build Zones, where we reward green infrastructure and stormwater management on private property with bonus development rights.

CODA

As I was finishing this article, RNZ published a story of a 44-day-long leak on Kent and Cambridge Terraces, where the Waitangi Stream is buried. Coincidence? Probably; the Waitangi is around 4m deep underground and there are a lot of potable water pipes here too.

Even so: could this be an opportunity to not just build back as it is, but for something better? Tom Greer’s render above is placed within the 40m wide corridor of Kent and Cambridge Terraces, so what are we waiting for?!

Processing...

Processing...

Auckland is very vulnerable to sea level rise and many areas will be lost and under water. Speeding up the loss of land is erosion and dredging. Dredging is very harmful and is happening in Auckland where the harbour is being deepened and the dredgings taken and dumped near Great Barrier Island. There is dredging at Pakiri and the sand taken to make concrete. Dreding speeds up erosion of a nearby shore just like when children dig holes in the sand at a beach the rim will cave in. Dredging a river speeds up the erosion of a river right up to the mountains. Land owners living beside the sea fear any erosion from storms or dredging nearby.

In the East Coast the dredges are busy and they are dumping sand and silt in the sea.

Singapore on the other hand dredged huge quantities of sand over many years from several islands, some of which disappeared, to reclaim land and increase their land area of Singapore by 20%

Our land is precious and we should be reclaiming land and not dumping it.

Mark Todd for Ockham wrote an article for Newsroom in 2021 and was reprinted on GA;-

Every year on October 1, when the spring rains ease and the ground hardens, hundreds of heavy machines roar to life on our city’s fringe. During the officially designated Earthworks Season which runs for seven months until the end of April, the equivalent of 10 rugby fields each day are devoured as Auckland sprawls ever outwards.

They clear the land first. Bulldozers, diggers, graders carve through anything in their path. Out Waimauku way on the road to Muriwai, there are trees in the way. It’s scrub to some, regenerating bush – mānuka, kowhai, ti kouka, ponga, teenaged totara, elderly macrocarpa – to others. On Western Heights and into Henderson Valley, vineyards and hundred-year-old orchards succumb to marching polystyrene-pillared armies — five-bedrooms, three bathrooms and a double garage — nibbling at the feet of the Waitākere Ranges. On the Shore, Albany approaches Silverdale which morphs into Orewa and spreads inexorably up the coast.

Now head south where Clevedon and Glenbrook and Pōkeno threaten to become suburbs – and Paerata is slated to become a town – and where the Pukekohe Hub, the 4,000-hectare food basket whose rich loamy soil produces more than a quarter of New Zealand’s vegetables, is assailed on all sides. Since 2000, New Zealand has lost a third of all its vegetable-growing land. Once buried in concrete, it’ll never come back. Death by a thousand diggers.

Clearly the notion that people want to go from one side of the road to the other is not occurring either to people in America or New Zealand. Possibly also South Korea but that before picture looks suspiciously like a motorway… which would’ve been uncrossable to start with.

It’s very easy to put informal crossing points on such designs. These could be pedestrian bridges, stepping stones, or even shallower fording sections designed for people to get their feet wet. Lateral movements across such street designs would be easier than a four lane arterial.

Wet feet fords sound like a whimsical feature of a fairy tale city or something Disney might include in Zootopia 2, but real people don’t like wet socks or people with wet feet walking in their shops. Not if there’s no need for it.

Stepping stones eliminate the wet feet issue but they have the same essential “able bodies only” problem. And if the water body that’s being daylighted is deep and/or fast flowing, the safety issue (particularly for children) especially because of the whole “slippery when wet” issue, is quite severe.

And, of course, it’s still “designated crossings only”. I looked up the South Korean example on Wikipedia and it turns out it was a motorway, Changing a stream of cars out for an actual stream doesn’t change the people-friendliness of the uncrossable stream at all. It severed the two sides of the street before and it continues to do so afterwards.

The reality is that waterways weren’t… er… undergrounded (Is that what it’s called?) for cars, they were undergrounded for people. The Ligar Canal/Waihorotiu Stream example in the post, for example, predates motorcars by about 25-30 years. There are very much tradeoffs to be made here (especially anywhere with a risk of mosquito borne diseases).

The Copenhagen design, if I’m reading it right, is a very different situation to this Wellington scheme. Basically, it’s a linear park in the middle of the road — which I imagine could still poses challenges for wheelchairs — that’s designed to flood during major storms. When people are actually out and about, it’s people friendly. When people are trying to avoid being outside, or even when it’s dangerous to be outside, it’s not… but there’s no people there, so who cares?

Maybe undergrounded water systems are a sufficient threat to human civilisation that they all need to be daylighted — I am not qualified to tell — but daylighting shouldn’t be the last thing tried* just because it’s the most expensive… it should be the last thing tried because it’s the most problematic for people. That South Korean example, according to Wikipedia again, turns out essentially to be a giant water feature, with more in common with that harbour fountain Wellington has than the Waikato. That is, they compromised on the environmental/ecological design features in order to produce something pretty:

>Some Korean environmental organizations have criticized its high costs and lack of ecological and historical authenticity, calling it purely symbolic and not truly beneficial to the city’s eco-environment. Instead of using the restoration as an instrument of urban development the environmental organizations have called for a gradual long-term ecological and historical recovery of the entire Cheonggyecheon stream basin and its ecological system.[12]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheonggyecheon

*water gardens, converting grass verges to swale, planted roofs, that Copenhagen style thing, etc. etc. as other mitigating strategies

Two quick questions, are multi-lane arterials with raised curbs friendly to those in wheelchairs? Or safe for children to cross?

We can all raise hypothetical arguments against things we don’t like very easily. The paper I wrote was an exercise in viewing a streetscape from different perspectives, namely improving water quality, increasing our connection to the natural landscape and providing for safer movement of flood waters during intense rainfall events. In doing so, I looked at our unique opportunity in Aotearoa to use Te Mana o te Wai as a lever, plus build on what has happened overseas.

Wherever we look to implement such ideas, they need to be place-specific, taking into account the original natural landscape, what people movement needs to occur (longitudinally and laterally) and what additional benefits we can gain (wellbeing, biodiversity, air quality improvements).

At no stage is anyone claiming that these streams are being restored to their natural state. That is physically impossible due to the urbanisation that has occurred. Instead, in some sense, it is right to view these as water features, in that they act to raise awareness of the original landscape and the effects of urbanisation, they provide other benefits such as reduced heat island effects, and they still need to function as an engineered system.

Sorry, I missed this part:

“Wet feet fords sound like a whimsical feature of a fairy tale city or something Disney might include in Zootopia 2, but real people don’t like wet socks or people with wet feet walking in their shops. Not if there’s no need for it.”

You know you can take your shoes and socks off before crossing a stream eh? Might be quite nice in summer.

In summer the point is moot because over here you’re supposed to wear jandals anyway.

Anyway, a proposal for daylighting streams that is more serious than a few renders is always going to include bridges. We wouldn’t be the first city ever to deal with a river flowing through the city centre.

With the inundation profile thing, I guess the idea is that this gets impassable due to flooding less often than the status quo.

This what Seoul did to transform from motorway to park and canal

Great video, thanks for sharing!

Both sides look fairly accessible. Doesn’t look “severed” at all.

Certain our city could benefit from this idea. We do not have the population intensity of Seoul, or the tax system of Scandinavia to ensure these fantastical possibilities can become reality. But as the biggest town in the motu, we need to continue to be aspirational, and with the CRL we will finally have a subway, which is a must have for all serious cities. What has been done so far down Waihorotiu to the Waterfront, and also in Takapuna, shows how water can be reintroduced into our public spaces, with Maaori led design, and a greater respect for the natural resources that have allowed us and our tipuna to build this place.

We need heaps more apartments by the way, they have a nice tendency to not suffer so much from extreme weather events *if adequately constructed

Bah humbug

Definitely agree we need more apartments, have a read of my thoughts about Ecological Build Zones in one of the other GA posts (linked in the article).

There’s always a way to construct things if we want. Leaving aside tax as a discussion, if we think about the multiple benefits that green and blue infrastructure provide then we need to more accurately assess how we value such things. It’s very hard to put a dollar value on wellbeing, or deaths avoided due to better air quality, or reduced road fatalities, or the feeling of a more “liveable” neighbourhood.

Thanks to Ed and Stu for a really good article. The legal and planning shift that is needed to give effect to this concept should be a focus of attention in building resilience into our towns and cities. The failure to recognise streets as places lies behind a lot of our troubles, together with our failure to recognise that the water cycle is always there, and cycling even faster now.

Aotearoa Urban Streets Planning and Design Guide is our best presentation of the concept at present, built on Auckland’s Transport Design Manual.

It should be easiest to put into practice in greenfield areas, but developers need to move their focus from residential yield to building attractive communities – that need not be a great burden of cost, if infrastructure and resilience were actually to be funded from development instead of from tax/rates to the developer’s profit.

Building such changes into existing urban streets can be very difficult, where the public land available is already overloaded with traffic lanes, frontage space and buried services, but does need to be tackled if the taniwha is not going to intervene forcefully. Waihorotiu might be looking for a new, large diameter ‘pipe’ to get down to the harbour….

All the tools to hold water in suitable places, whether streets, parks or landscaping between buildings will need to be explored and used, if we are to avoid demolishing extensive tracts of untenable housing at huge public expense and private disruption.

Thanks! Agree, we need a shift in how we build for resilience when we plan our urban areas. Understanding the historic buried streams that are all across our urban areas is a start

Interesting post thanks Ed and Stu.