It’s important to give credit where it’s due. Auckland Transport’s Safer Speeds team deserves credit for a life-saving intervention that’s been flying under the radar, even as news headlines highlight the ongoing avoidable and heartbreaking harm to people just trying to get where they’re going.

I’m talking about these eye-catching statistics that came along with the recent safer speeds consultation, which deserve much wider coverage than they’ve had:

AT has found that roads where speed limits were lowered on 30 June 2020 have experienced a 47 per cent reduction in deaths* in the 18 months following the changes, a reduction in all injury crashes of more than 25 per cent and greater than a 15 per cent reduction in serious injuries on these roads.

Total deaths and serious injuries (DSI) have reduced by more than 20 per cent.

Rural roads where speeds were changed on 30 June 2020 have seen a 71 per cent reduction in deaths and more than a 25 per cent reduction in serious injuries.

* Annual figures for the period 30 June 2020 to 31 December 2021, when compared to the prior five-year comparison period.

In other words: people are alive today who would otherwise not be – simply because speed limits were lowered on the roads they happened to be travelling on. This is nothing short of miraculous.

We don’t know who they are, because we don’t need to.

No names, no faces; because no headlines needed when you make it home alive.

Hey everyone, unfortunately we did see an increase between 2020 and 2021 (during lockdowns) but overall the deaths and serious injury statistics on roads where speed limits were adjusted have reduced. JR*

— Auckland Transport (@AklTransport) February 23, 2022

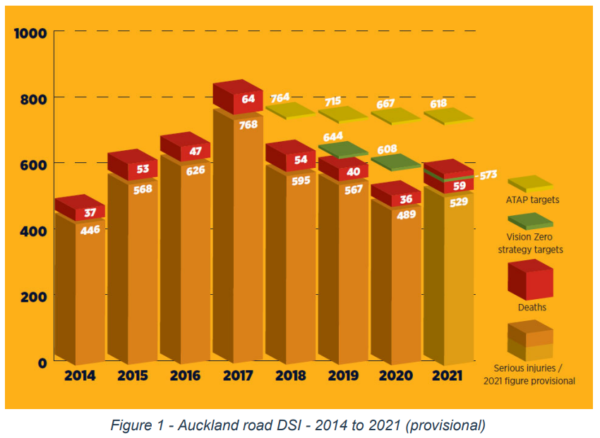

This is extra striking, given that it happened against the backdrop of an overall increase in road deaths and serious injuries. As Auckland Transport reported to the Board in March this year:

During calendar 2021 there were 59 deaths on Auckland’s roads, more than 60% higher than 2020 and the highest level of road trauma since 2017, as illustrated by Figure 1.

The other thing to note is that rural roads didn’t see fewer crashes as such, just less terrible outcomes: “on our rural network… the overall number of crashes is similar to pre-implementation, but the overall severity rates have reduced.”

In other words, with their work on lowering speed limits, the Safer Speeds team has been mitigating the effects of a transport system (and sector) that seems to be otherwise heading in the wrong direction.

Moving from piecemeal progress to wholesale wins

So while the overall picture is still alarming, these successful stats must give AT the confidence to take a much faster and more universal approach to implementing life-saving policy.

When it comes to winning the public confidence for systems change, the key is in demonstrating benefits as quickly and widely as possible. This means leading with a bold vision, and implementing an extensive programme that reaches everyone. It means using clear and strong messages: we can look after each other better on the roads. It means pushing beyond early public tentativeness to achieve results: these statistics speak for themselves. And it means trumpeting those results: we saved this many lives.

So far, AT has taken a step-by-step approach, phasing in safer speeds along three main paths:

- treatments in outer areas, where development has turned rural roads into urban streets but the speed limits were left unchanged, and where there’s general understanding that country roads have been operating with an unsafe limit for too long.

- “easy wins” in urban areas, e.g. the city centre and selected town centres; quiet residential zones with minimal rat-racing; schools around which speeds are already moderate; etc.

- targeted areas which have been “engineered” to encourage slower speeds, such as Manurewa.

The “easy wins” approach made some sense as an initial short-term strategy, to help show progress and grow public support. But the longer term strategy to actually save lives needs to be evidence-based. So, this is a critical moment to assess the evidence. For example, to shape future consultations and communications, it would be good to know things like:

- Where have the biggest speed reductions taken place? Were they from the “easy wins”, or in the more rural areas where “easy wins” weren’t the strategy – or both?

- On city streets where limits were lowered without other major engineering changes, have speeds fallen – and by how much? Does every driver take it down a notch when the limits were lowered, or is it mainly the extreme speeders at the top end?

But what does the public think?

We hear a lot about how you have to “bring the public along” when making changes, even ones that will save lives. After AT introduced the first tranche of safer speeds and accompanying road treatments in town centres and neighbourhoods, it commissioned surveys to find out what people thought. The results may (not) surprise you.

In the town centres, people said the streets felt safer – especially, but not only, around schools. They also noticed that more drivers were observing the limits, and said it felt significantly friendlier to walk and bike, with 1 in 5 respondents saying they were walking or biking more often.

And the neighbourhood surveys were even more striking:

Clearly, one of the ways to “bring the public along” is to actually make the change, so they can see that it works. So far, so good.

With one caveat: it’s crucial to check in with kids – because children are the public, too, as we are reminded in a fabulous new piece of research by Dr Julie Spray about the Pandemic Generation. Children’s voices are something we could stand to hear a lot more of in the transport realm.

So… why are we even talking about this? Why not just do it everywhere?

Good question: does every single street need to jump through a consultation hoop one by one? Why not just roll this approach out all over, given we know safer speeds save lives? (And creates a better environment for walking, scooting, rolling and riding – and reduces noise – and saves on petrol – and lowers emissions – and so much more?).

Part of the issue has been the legislation. On the one hand, it empowers AT to make these life-saving changes:

Under the Land Transport Rule: Setting of Speed Limits 2017, AT is legally obligated to investigate road speed limits and, where current road speed limits are found to be not safe and appropriate, it must make changes.

On the other hand, it requires a local authority to be confident that drivers will, on average, not go more than 10% faster than the new limit. This particular fishhook has slowed down the adoption of wider safe speeds – for example, when a local authority believes it needs to physically change the road to get drivers to meet that threshold, but the budget just isn’t available.

The good news is that an update to the legislation is on the way – and hopefully we’ll see new rules in place this year that will lead to more efficient and better coordinated speed management. (Updated 21 April 10.30am: sounds like the new legislation has been signed and is on its way!)

But even within the existing legal framework, bold things are possible. As Heidi wrote here back in June 2020, you don’t always have to change the road itself to change people’s speed:

research by Glen Koorey found drivers base their decision on what speed to travel at from a combination of different factors. The road design is not as big a factor as posted speed limits, the level of enforcement, and “the general societal/cultural norms for respecting laws, [and] perceived appropriateness of the speed limit.”

You can achieve lower average speeds by treating whole areas at once, and with strong communications clarifying that 30 km/hr is the appropriate Vision Zero speed limit for cities. People get the message… when they’re given the message.

And then there’s the growing body of knowledge from other cities that are rapidly civilising their transport systems. Low traffic neighbourhoods and similar treatments can be delivered very cheaply, if done tactically. This means that – even within the existing legislation – the same money for engineering treatments could have been spread much more widely.

First (and last): do no harm

Amid a rising road toll – a wicked problem, with many factors – the proof that safer speed limits are working is a ray of hope. Auckland’s journey to safer speeds started with the understanding that it certainly couldn’t hurt. Now we have evidence beyond a shadow of a doubt that it actually saves lives.

So, what do we do with this knowledge?

In medical studies, there’s a point when interventions show such a dramatic benefit that it actually becomes unethical to keep giving the “control group” the placebo or hands-off treatment. If you were testing a Covid drug, for example, and saw figures like those at the top of this blog post, you’d have no trouble halting the experiment and making everyone better.

Now that we know what we know – and with more empowering legislation on the horizon, surely we can end the street-by-street experiment on safer speeds and go all out?

Anyone in a governance or leadership role should feel confident that nothing now stands in the way of delivering life-saving benefits to all Aucklanders without fear or favour. Just do it.

A departing executive whose overarching aspiration was safety might even consider it as a parting gift to the city. Why not?

And an ordinary citizen could share this knowledge with friends and neighbours and children and workmates, which would help make the next round of consultations and conversations about speed limits a lot easier for all of us.

Because who knows – the life you save might be your own.

Processing...

Processing...

100%

Lets hope that the New Setting of Speed Limits Rule will actually allow for a bolder approach. I worried that the draft that was consulted on looked like it was just swapping a lot of unnecessary public consultation to a make a “speed limits bylaw” with a lot of unnecessary public consultation to make a “speed limits plan”. When we already know that in response to the consultation lots of grumpy status quo advocates will call for speed limits to stay higher.

Speed limits should be more of a science and an ideology; which means there really is no point in public consultation at all – if the road controlling authority’s experts know what the safe and appropriate speed limit should be then who cares what the non-expert general public thinks about it?

The Government’s response to Covid has shown this works – would we have been one of the most successful Covid countries in the world if we had consulted on the merits of lockdowns before putting them in place? So why consult on speed limits?

I hope so, too, and the people working closely with the material seem to be positive it will. But in any case, the actual legislation on consultation requirements is pretty minimal. Most of the unnecessary public consultation has just been due to an AT management approach on how to respond to the legislation.

I think one of the things preventing faster progress has been AT’s aversion to applying Vision Zero speeds to the arterial roads across the city. On our arterial roads we have people walking, cycling, including children going to school, etc. We have people needing to cross to the bus stops. Vision Zero is clear on what the speed limit should be – it is 30 km/hr.

AT’s responsibility is to deliver safety for these people – and everyone wins if they do so. The Safer Speeds team are certainly wanting to deliver that safety. Yet here we are, over 4 years since the Safety Review, and the organisation is still hung up on pussyfooting around the business community.

Human sacrifice to the gods never achieved anything in any other culture. I don’t know why people think it will here.

I spoke to an AT safety engineer last year working on this lower speed program. I asked when the arterial roads will be getting speed limits in line with the international transport forum recommendations (ie if it’s street with homes that’s not separated, 30kph max). He said never, the arterial roads need to be 50kph despite ATs stated policies of vision zero. I don’t understand how they can get to the that position in conext of vision zero.

So we need to elevate this problem. I seem to have hit brick walls.

Can you put that comment into an email to the safety engineer and query why?

The excuses I have received include blaming it on the mayor – which is rubbish because AT’s job would be to set the record straight with the mayor if he was saying this.

Hi Jak. If you received feedback that arterial roads “need to be 50km/h” this is not accurate. I apologise if this message was sent. There is also some confused messaging from some elected members that “all arterials are planned for 30km/h”. This is also not accurate. A tailored approach will be required I expect, taking into account road / location characteristics, whether there is walking and cycling separation etc. Our first speed management plan, which we are hoping to share publicly late 2022, will provide the best indication of approach with some real world roads across our region.

Cool, thanks Nathan.

I hope Vision Zero has been applied free of all political filters, and that if the organisation has required one be applied, that the team has pushed back. 🙂

That’s great to hear Nathan.

Based on my reading of the ITF recommendations, the vast majority of arterial will need to be 30kph.

Wil an Arterial like New North road have 30kph speed limits? Why is this not being included in the arterial plan?

A road like Tiverton road, where the homes are separated by a sub road, 50kph could be appropriate.

Hi Translex, I think the key difference is that, under the new Rule, you can consult on the overall speed mgmt Plan for your road network once and then get on with implementing it (Rule only requires a Plan to be reviewed, updated and reconsulted once every three years). Contrast with at the moment where every individual street has to be litigated over during consultation – and then another bunch of streets, and then another bunch… So procedurally this new Rule helps all that.

Requiring all roading authorities to prepare an overall Spd Mgmt Plan also helps them to come up with a consistent logic and rationale as to what they are doing and why, rather than taking an ad hoc “whack a mole” approach to changing some roads but not others. This is pretty important when you are trying to explain the “why” bit to elected members and the general public (esp. “how come you’re changing this street but not that one?”). We helped Taupō District recently prepare a speed management plan, and having those overarching principles of what different speed limits are used for and what to prioritise first was very helpful when engaging with key stakeholders.

There is always a compromise between safety and efficiency,for too long ,efficiency has always held sway,and the transition towards safety,has been met with pushback. Figures like these, show just what is possible, the irony being that by slowing down,and giving other modes a chance,the motor vehicle journey can become faster.

Always the groups,that debate,the percieved increased journey times is lost productivity,as opposed to sitting stalled in traffic.

One of the classic defenses for maintaining status quo,is going slower,increase emissions,as engines are running for longer,l guess though that sometimes “you can’t fix muddled thinking”

Re: travel time. Interestingly this is comment is in line with what we have measured in the city centre mid-2021 (before lockdowns hit us again). The bundle of key roads monitored saw a mix of slightly slower and slightly faster travel times. The faster travel times weren’t actually expected – but thinking at the time was that it could be the influence of the lower speed limits on driver behaviour – i.e. smoother driving, which is actually quicker overall.

Jolisa, I’m sure you didn’t intend to but I think you understate the community support for lower speed limits.

The results of AT’s recent consultation (round 2) showed, in several suburbs across the isthmus, 90% support for lowering speed limits on residential streets from 50 k to 30 k.

So, yes, AT should just get on with it. 90% support for change is monumental.

(I read somewhere that many of the negative comments were, unsurprisingly, from people driving through rather than living on or near the streets they were commenting on).

Can I also say: that junction in Nelson is hideous. I’d hate that on my street. What we need is consistency. Every single one of our shared paths and cycle paths seems to be a different design, with different markings, different colours.

The Nelson intersection was a very quick, very cheap trial installation. The only other choice was to leave the massive sweeping curves in.

Just wait until the Nelson intersection is filthy, those colours will look even worse then.

Morning chaps, I’ve added a photo of a tactical treatment in friendly earth-tones, featuring wooden planters built by the local Men’s Shed, to clarify that we can calm traffic in all sorts of ways that suit all sorts of aesthetic demographics.

(It might be useful to know that the Nelson South project centres on a kindergarten and an intermediate school, and is complemented by other art projects and installations designed by and with local children – so in that sense, it reflects the community most engaged and empowered by the change.)

lol, thanks Jolisa

And if anyone else is interested, when they make those curb buildouts permanent, they can do it for cheap and very nice looking.

Best example I’ve found is in One tree hill (the suburb)

https://goo.gl/maps/8nz6VAtjJGeiiE1B7

No drainage changes, nice trees.

(not being sarcastic with that thanks either just hard to capture tone in text, genuinely adds to the article well)

“For those allergic to bright colours in a roading context” lots, love it thank you

Where does this 90% figure come from? It’s believable but I couldn’t see the feedback? I’m mostly interested in the Pt Chev feedback (mostly about keeping Pt Chev Rd 40 so traffic stays on it rather than going down Walford)

Why would you want to plug for a speed limit that does not match the evidence for what is safe? That is a proposal that puts our people at risk.

The issue about Walford can be easily solved by putting in a modal filter at Meola Rd. That would make the bidirectional cycleway much safer, too, and encourage so much mode shift that driving would be improved, too.

+1, if we don’t want rat running, we should just block rat runs. This really isn’t hard.

The 90% is of course of respondents which is a very small usually motivated group of people – not 90% of the general or local population. Agree 40kph is a more sensible speed limit in general and far more likely to be adhered to. Just look in the CBD where 30 is seen as the minimum speed. Agree that more could be done re treatment of rat runs, but needs to be targeted and agreed by local residents.

Can we encourage the NZ Herald to publish this good news as a refreshing example of a “controversial” change that has worked. One that should from now on, only be “controversial” if it is not rolled out more widely across the city

No they will be busy making bad faith arguments about the Auckland road toll (their term) shows that lower speed limits have failed. Intentionally missing the fact roads with lower limits were not where the deaths happened…

Thank you Jolisa for the comprehensive post. There is a small, dedicated team progressing the Safe Speeds work at AT and it’s easy to get disheartened by the media and entrenched sentiment. This is a massive mindset shift for Auckland and NZ. But as you say – where this shift has been made already, the road trauma statistics and verbatim public feedback heavily support the changes. I am really looking forward to the (hopefully) imminent legislative changes, as the current approach to speed limit setting is quite restrictive and cumbersome, and frankly we are not at the moment meeting the demand that is out there for safe streets. Thanks again.

Hi Nathan, thank you and your team for progressing this, I am sure that the challenges that you noted can be disheartening! Hopefully your team can get the legislation (and budget) to truck on with getting safer speed limits across the city.

+1000 Thanks Nathan.

Cheers Nathan – I’ve added a vote of thanks to you and the team further down in the comments, but wanted to also put it up here where more people will see it. Appreciate your work, both with the programme and here in the discussion arena, to instil confidence and reward optimism. Onwards!

I totally commend the Safe Speeds team @ AT. You’re turning the tide on traditional traffic engineering (faster = better) whilst having to deal with a vocal minority who dislike change. Thank you.

They selected roads that had high fatality rates. Road deaths are rare events so Regression to the Mean suggests the number of deaths on these roads would be lower in a future period regardless of what AT did. Sorry to rain on their parade.

They also selected roads where the speeds were already down close to 30 so they could make the change without engineering measures. Also, “all injury crashes” were down 25% – they aren’t “rare events” unfortunately, so Regression to the Mean won’t apply.

I was taught that injury crashes are random and rare events and regression to the mean does apply. The difference between an injury and a non-injury comes down to things like the age of the person and whether there was a pole there. Every team pushing an innovation makes this claim, whether it is red light cameras, black spot studies, speed cameras, safe systems etc etc.

“I was taught that injury crashes are random”

Well that was bad teaching, then, wasn’t it?

All crashes are random in the statistical sense. The issue is whether they are rare enough that a large reduction is more likely to be the result of natural variation in a random event or a result of an external change. Given that AT changed speed limits on something like 3,000 km of roads, injury crashes are probably common enough that the expected annual variation would be small. Of course, AT could have used 10 years worth of data to show this.

Crashes are not random in the colloquial sense in that they tend to cluster and have similar causes. A similar comparison might be days with temperature over 30 degrees. If we count how many times this happens each year, then we know that, over time, it is increasing. However, the random year on year variation is so much larger than the trend that you need a really big sample size to draw meaningful results.

You are correct Miffy in that a key focus area has been roads and areas with poor safety performance. In particular our rural roads, many of which have simply nonsensical speed limits, where simply putting up new signs has dramatically reduced the road trauma. The comparisons are taken across multiple years (e.g. a five year period before the changes) to average out the year-to-year ups and downs, so at this stage we are expecting the benefits to be sustained (i.e. not trend back to historical levels). As Heidi notes, there is also a focus on ‘correcting’ speed limits where drivers are already travelling well below the speed limit – which helps remove some nuisance speeding, encourages active modes (in particular walking – from the survey work completed to date) – many of these areas may not have a strong history of road trauma but until the speeds are set to safe level the risk is certainly still there.

Awesome to hear the focus on correcting the limits like that. Quite often I find myself doing a safe speed on a local street (non arterial) with kids and dogs around with an extremely aggressive ute driver behind me, clearly angry that I dare to do under the posted limit.

Limits have changed in the public mind from “the max speed you can safely do” to “the speed you should be doing”. They need to become more granular and generally lower to reflect the shift in mentality.

That really is all wonderfully good news. Couple of questions though – firstly, why did crashes (deaths, serious injuries etc) increase during COVID lockdowns? eg AT’s comment that “…unfortunately we did see an increase between 2020 and 2021 (during lockdowns)”. Anyone know / understand what is driving that? I thought that we were all staying at home and not driving much at that time?

Second question – is it just my imagination, or are things louder out on the streets now compared to pre-pandemic levels? There seems to be lots more boy racers revving engines, and loud un-mufflered motorbikes farting and rumbling on the streets. I feel like the regular car noise has been replaced by idiots making noise to a far louder volume.

my speculation is that the average speed of vehicles has risen due to the lack of traffic and that is to blame for the overall increase.

On the noise front, we should start doing automated vehicle noise enforcement. It’s a thing overseas.

I think you answered your own question. There are many factors involved, but a lot of it is to do with car culture including elements of domination, freedom over restraint, and the thrill of speed.

Data coming in from overseas early in 2020 presented a clear need for AT to impose emergency speed limits and to make emergency changes to street layouts where needed. The emptier streets were, otherwise, going to be treated as drivers’ playgrounds. WK made sure it was easy for AT to do so.

Unfortunately, AT treated Covid as something that would be “over soon” referencing NZ’s strong response as a reason any temporary measures would be able to be removed quickly. They didn’t take the situation, nor their responsibilities, seriously.

A few other major noise contributors:

-Diesel engines

-off road tyres

-chip seal on roads that were asphalt.

Independently these add noise to each vehicle movement.

On the first question – As Heidi mentions, there are probably many factors involved. I did read some overseas research which indicated that – very generally – crashes dropped during lockdowns with less cars on the roads, but the severity of collisions increased as fewer cars resulted in more free flowing traffic conditions and higher vehicle speeds (https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/2021-10/Traffic-Safety-During-COVID-19_Jan-June2021-102621-v3-tag.pdf).

Yep, a common trend elsewhere – fewer crashes overall due to less traffic but a much greater steer towards serious and fatal ones due to higher speeds. Another case where congestion is actually your friend… Remember also that the lockdown periods brought out greater numbers of people walking and biking, thus increasing their relative exposure – active mode injury numbers in Auckland continue to be a big problem.

One point is I think the noise of specialty racer sounding mufflers etc are to make up for the fact it’s harder and harder to race/speed around the place.

Auckland doesn’t have a noisy car problem compared to Christchurch. Living in this city feels like a 1970s time warp versus Auckland; Car clubs still exist and thrive. Touring in processions of 100s of cars all hours of the day and night is a thing. Motorbikes thunder around, jet boats on the rivers and dirt bikes on the river banks. Petrol being burned everywhere; climate change be damned. On the flip side there are far more cyclists and recreational walkers than I’d ever seen in Auckland. And more cycle ways. go figure!

Great to see the difference this is making.

We do have a problem with streets that have been designed for driving speeds that are not really safe. Traffic calming has reduced driving speeds on some of these where that is needed. Speed limit change can reinforce this. Better data noq available on actual driving speeds can also help to identify which streets do and don’t need Traffic calming to support Speed limit changes.

Some of the difficult streets are the urban connectors – the long arterials where they don’t have land use to give them Activity street status that supports alocal low speed limit. These are the streets with historical ribbon development. Too many driveways make them unsafe. They are also the streets with frequent buses, so need people coming to them. They also need expensive low speed safe crossings to serve the bus stops. Dropping the speed limit to 30 k for the full length of these Connectors without physical controls would be a hard task and would significantly affect people’s journeys. Are enough people willing to support that now? Meanwhile, targeted improvement of crossings with physical speed controls is making safe crossing available.

Making low speed streets look different from 50 k streets is also important. It has been hard to get that message across to developers who build new streets, but it is happening now, so many new residential streets can be made 30 k straight away. The new Speed limit rules will allow the developers to put up the speed limit signs, so AT doesn’t have to find the money for that.

Nathan, great to read your comments to this article and it’s heartening to see someone from AT fronting for the organisation on this blog. So often criticism of AT here feels like farting in the wind and we all get wound up by the lack of response. Your clear reasoned answers are well appreciated. Thank you!

Yes, what MrPlod said – thank you Nathan, really appreciate your contributions both here and with your colleagues in the programme. Onwards and upwards! (Or, mostly downwards, when it comes to the speed limits.)

+1000

Again, all the nice lower speed limits, fancy traffic calming measures are nearly all in the wealthier suburbs and mainly within the isthmus. Go to South Auckland, Mangere East, Papatoetoe, Otara, Mangere and there’s next to nothing. Maybe the only the wealthiest suburbs get them and flash bike paths?

One challenge with a regional programme such as Safe Speeds is balancing risk and regional equity. I would suggest the comment above Tony T is inaccurate – but you may not be across the latest, as there is a lot going on. The Phase 2 changes, approved three weeks ago, includes further investment in Manurewa, Ōtara town centre (previously having had speed calming and other safety measures installed), plus a number of school zones and southern rural roads. The third phase, consulted Feb to Apr 2022, includes a heap of proposals for the south. The best way to visualise this is our mapping tool here. Hopefully this helps: https://atgis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=a13aa8469db642f283ef3ad241b71882

Not to rain on your parade, of the 4 suburbs you named, speed reviews have already been done in parts of 2 of those suburbs, with consultation just now finished in parts of 3 of them. Mangere has also, in the last few years had 2 different large bike projects built.

Yes there is a good correlation between Greater Auckland contributor’s suburbs and those chosen. Maybe a plan from AT to keep lobbyists happy!

I fully understand why many central city roads are now 30 it makes a lot of sense, it really does. There are so many hazards in close proximity to moving vehicles.

But. Why did dead straight and flat rural roads with good visibility and no one around go from 100 to 60?

It’s just tedious for locals to go anywhere now, and difficult to keep the speed within the new limits.

And now it seems speed is being recorded with pneumatic traffic counters, is this planning for permanent speed cameras, or potential to return to the original speed limits? As no one is dieing out here due to inattentive speeding.

I get that when a road starts to twist and turn you might want a lower speed than an open road at that point, but not the entire road. This was in some of the public feedback to the proposed changes, of which 100% was opposed to, but it still went ahead.

I am trying to be helpful when I suggest banning very cheap tyres, having practical driver training, installing clearer road and corner markings, and better road surface maintenance is what will make the difference out here. It is also my observation that almost all of the accidents here are small ‘city’ hatchbacks, and by that I mean 5 of the 6 that crashed into our property in the last year.

I hope someone sees this and is either able to explain why the changes happened, or relay some rural logic back into the decision committee, ideally both.

If you want to talk specifics about your road, then you’re going to have to give a rough address / google maps link. Fully understand why you wouldn’t want to, but speculation is very difficult when theres not enough context.

Now for wild speculation:

The point isn’t to solve “black spots” any more, rather change swaths of roads to make the whole system safer and be more proactive in general.

“Rural” could be pretty dense rural there with a driveway / accessway ~ every 100m or so. Cars start to perform pretty poorly in side impacts once you get to speeds faster than 60, lots of intersections, lots of chances for side impacts.

Its really busy and not directionally separated.

Didn’t want to have multiple limit changes in a row 60-100-60 again

Relatively narrow seal.

There could be hundreds of reasons. There could be none. Who knows without seeing the road.

Generally if dead straight and flat rural roads are being posted at 60 km/h it will be incredibly high roadside risk. This typically means lots of driveways or things that hurt very close to the road.

Here is one where roadside risk is really high (and where the risk isn’t immediately obvious) https://goo.gl/maps/D57pbFDJ6wf6q8JX8

Here is one that is probably based on access density https://goo.gl/maps/Tn2MyfVc4NZF556X6

I can’t say I was expecting to actually get some meaningful suggestions to answer my questions so thank you both for your insights.

“and difficult to keep the speed within the new limits.”

Wow, a great indicator of the overall dangerous incompetence of NZ drivers

I am suprised you didn’t think the best indicator was how many people have crashed into our property in the last year alone.

These people were going about 60-80kmh on a 100kmh section of road.

Your conclusion about driver competence is correct however.

I am not sure how much open road driving you do, but I’m sure you can appreciate the challenge of sticking to 60 on a section of motorway you have spent your whole life driving on at 100.

I’ve just driven back to Auckland from Napier, which now has an 80km/hr along most of the Napier-Taupo section.

I found it a very pleasant trip, no drama with trying to “keep up with the speed limit” or “holding others up”. And guess what, it didn’t take much longer, if any longer at all.

I just wish that AT would make the obvious changes first, and if they are doing other improvements then consult on speed at the same time – you know, take a whole system approach to the proposals including safety at the top.

It appears the consultation requirements are far less onerous…

https://www.nzta.govt.nz/assets/resources/rules/docs/setting-speed-limits-2022.pdf

How will lowering speed limits from 50kph to 30kph in a small rural town with no recorded road crashes improve safety? People have asked for a pedestrian crossing outside the school for years which has been declined. Surely the best improvement is a reduced speed limit around the school during hours that children are going to school and home. An undulating terrain makes a constant 30kph difficult. What is being done to make us safe from drunk or drug drivers and mobile phone drivers?

It would likely improve “perceived” safety, a key determinant when people choose to walk or cycle. It may also prevent future injuries. Safer speeds only around school opening and closing times seems to be saying children should only be free to travel independently during those times?

Thanks Bevan, while Leigh has always had a good walking population we were unable to get 400 metres of footpath to a local restaurant/cafe. This is now at the planning stage after 10 years. The increasing number of cyclists are thwarted when trying to ride the unsealed roads by lack of maintenance. Ruts, potholes, corrugations and bare clay pans dominate since regular grading stopped. Now the gravel tossed haphazardly on the roads washes to the edges making a further hazard for cyclists. Constant complaints logged with AT do nothing. Leigh township is quite undulating and I find speeds of over 40kph while freewheeling downhill on a bike the norm. I won’t feel any safer cycling alongside cars as drivers concentrate on trying to maintain 30kph up or down the hills

You’re bringing up some good points, Tony. Road maintenance is a huge burden that we as a society need to get our heads around. We have too high a length of lane km per per person, and need to reduce that number so the quality of the maintenance can increase without the cost going through the roof. And yes, the demand for footpaths is outstripping AT’s willingness to invest in them. Yet they do state that walking is the fundamental unit of movement, and that we all have a right to safe walking. Basically, money needs to shift from projects that are all about traffic flow to projects that deliver the ability to move around safely and sustainably.

You should feel safer cycling alongside cars at 30 km/hr. The drivers have far better peripheral vision, their reactions have a chance to kick in before the car has gone far, and the stopping distance is far less. At 30 the likelihood of a collision is far lower, and the outcomes are far less traumatic. “Drivers concentrating on trying to maintain 30 km/hr” might feel like it’s a biggie, but it’s not. Once people are used to travelling at that speed, it won’t seem so odd. In NZ, drivers have become accustomed to driving at speeds that are inappropriate for the visual cues they are receiving. That needs to be reset.

And also, an important point about maintenance is that slower cars will do less damage, and the more modeshift we can encourage (with slower speeds) the fewer cars doing damage, too. But of course, the paving needs to be appropriate for cycling. Which is a big issue that needs tackling. Chipseal should be left for just the motorways and limited access highways. It’s inappropriate for anywhere where people ride bikes. Or for walking, bar rural areas where walking numbers are very low.

This is it: “Basically, money needs to shift from projects that are all about traffic flow to projects that deliver the ability to move around safely and sustainably.”

Agreed. But the money won’t shift whilst NZTA sticks with its investment assessment methodology that is designed to give the highest cost-benefit ratios to roading projects.

The largest benefits in NZTA’s calculations are travel time savings for motorists. These are calculated over the next 60 years (ignoring induced traffic that soon erodes the travel time savings and that the congestion bottleneck is typically moved down the road).

Consequently NZTA continues with business as usual and doesn’t deliver on the GPS 2021 priorities of safety, active & public modes, mode shift and reduced emissions because their cost-benefit ratios are too low.

NZTA prides itself on delivering “Value for money”!

It’s my experience but I’ve noticed that speeds along Beach Rd in the city centre have dropped somewhat. There is a 30kph limit along here (in line with much of the city centre), but no engineering was carried out to narrow the very wide road.

Sorry Victoria, we’ve moved on from last century transport thinking.

I think you’ll find that the 130km/hr roads in Europe are rural motorways. Grade separated interchanges, and directionally separated. They have lower limits at night and in the rain, urban motorways are generally 100km/hr or lower as well, and they have other measures to ensure speed compliance. Like mechanical speed limiters on all heavy trucks which have a limit of 80km/hr. They only places in NZ that would generally meet the 130km/hr standard would be Auckland to Hamilton south of the Bombay’s, and the Wellington northern corridor out of the city. But would probably need entirely different barriers.

The vast majority of the state highway network in NZ would be 80 or 90km/hr by most European standards, and with different limits at night and in the rain. And almost every rural local road would be the same. So careful what you wish for on that front. NZ’s limits mostly are far higher than would be standard in Europe, it’s only the most prominent roads where our limits are lower. Even in a lot of American states non directionally separated roads are mostly 90km/hr.

“the problem is better solved by removing the chance of the impact, not reducing the speed of it.”

Agreed, Victoria. Protected cycleways, if you are keen on a 2022 solution.

As I’ve noted in other articles we urgently need a mandatory nationwide Vision Zero/zero carbon design standard for new builds and retrofits that works for all modes.

Two questions:

Were the numbers independently verified or are you marking your own homework?

Is the raw data you have based your stats on publicly available?