This is a guest post from Geoff Cooper, Director of Economics at PwC, on work he’s done looking at viewshafts.

The Journal of New Zealand Economic Papers recently published ‘City With A Billion Dollar View’ by Geoff Cooper (Princeton University, but now at PwC) and Kabira Namit (World Bank). Geoff lays out the policy, the analysis and the case for changing Viewshaft E10.

A slice of the city

If you are like many Aucklanders, you’ve probably never heard of viewshafts or cared to think how they influence the city you live in. An obscure planning policy, hidden in thousands of pages of planning rules. Sounds dull.

But have you ever wondered why half the city centre is the same height? Why the western side of the CBD isn’t as dynamic as the bustling Britomart or High street? Or why living in Wynyard quarter is so expensive?

Viewshaft E10 is a good answer to all of these questions. It has sliced the top off the western side of the city, to give southbound motorists waiting to pay a bridge toll in the 1970’s and 80’s a look at Mount Eden. The booths have long gone, but the view remains, with a price tag of $1.4bn.

Viewshafts in Auckland

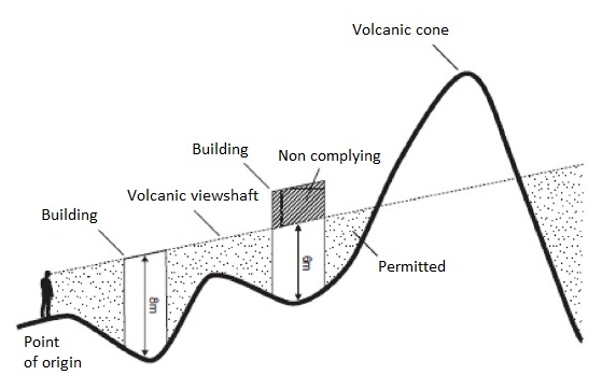

Aucklanders love looking at volcanic cones and the Unitary Plan protects 80 such views across the Auckland landscape, covering about a third of all private land on the isthmus. The policies themselves are three dimensional in space and prohibit development over a certain height (Figure 1).

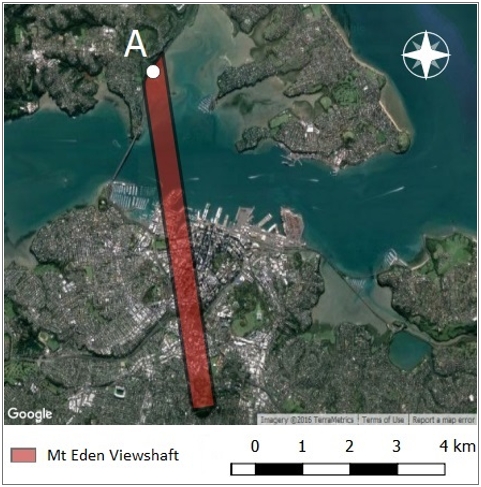

Our paper attempts to unpack the impact of these policies and present a methodology for their evaluation. To do this, we focus on one viewshaft, known as E10, which protects views of Mount Eden for southbound motorists approaching the bridge around the Onewa onramp (Figure 2). E10 was purportedly located behind the old Auckland Harbour Bridge toll booths, when motorists were forced to slow down and take in the scenery (Figure 3).

The Impact of E10

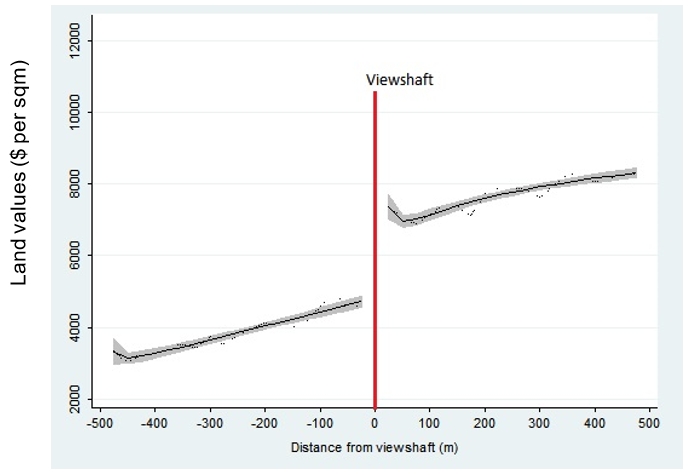

The analytical approach is a simple one. We use an econometric technique called a regression discontinuity – but it’s basically just a comparison of land values on either side of the eastern edge of E10. By controlling for other things that affect land value

(on either side of the discontinuity line), the approach allows us to attribute the remaining difference in land values to the policy.

Figure 4 is the key finding. This chart plots the land value of properties in the CBD against distance from the eastern boundary of E10. Properties under the viewshaft are on the left of the red line. A property on Queen Street is on the right. The impact of the viewshaft is striking. Land values drop by 40% next to E10.

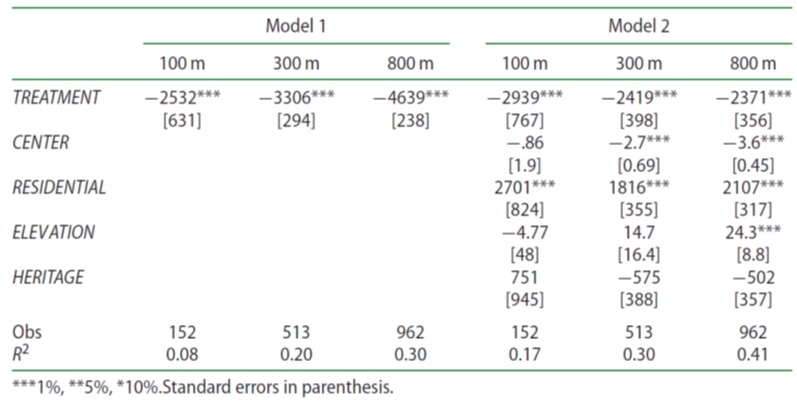

The full numerical results are in Table 1. Model one is a simple comparison between the treatment (properties under the viewshaft) and the control (properties outside the viewshaft). Model two includes controls (with improvements in precision). The distances (100m, 300m and 800m) correspond to the amount of land included on either side of the eastern boundary of E10.

What do we notice? The effect of the policy (designated TREATMENT) lowers land values across all specifications and is significant at the 1% level. Model two provides a remarkably consistent effect of the policy, ranging from -$2,371 to -$2,939 per square meter.

Calculating the cost is now straightforward. We multiply the effect of the policy with the amount of private land under the viewshaft (641,000 square meters): $1.552 billion.

Calculating E10 Benefits

So far the analysis has been about costs. But we protect views because it is worth something to our residents. We identify two types of benefit: sight line benefits and volcanic view benefits. Sight line benefits accrue to properties on the border of E10 because these properties enjoy protected views into the viewshaft (Figure 5). You can see sight line benefits in the data. Figure 4 shows a slight ‘out of the ordinary’ increase in land values on the E10 border (in the control). To be sure, these are not the intended beneficiaries of the policy, but they benefit all the same. Using a similar technique to that described, we value these at $186m.

Volcanic view benefits are more tricky. E10 benefits motorists, so land values cannot be used. Instead we look to other viewshafts in Auckland. If we can find an effect on land values elsewhere (where the targeted beneficiaries are not motorists), we can use them to estimate benefits for E10. Under various specifications and a range of models, testing the entire viewshaft regime, we fail to find any impact on land values for those that the policy is targeting. This is a striking contrast to the costs – which are loud and obvious.

Despite these efforts, the benefits analysis is inconclusive. Volcanic viewshaft benefits could be so small and distributed, that they are undetectable in land markets. Therefore, until better information is available (such as willingness to pay data), we live in a world where debate and speculation about viewshaft benefits will continue.

To assist with decision making then, we change tact, asking, ‘what amount of benefits would we need to see, such that E10 would be a good policy?’ For this we turn to transport data.

The average flow of traffic into the CBD across the Auckland Harbour Bridge in 2014 (the year of our data) was 82,147 vehicles per day. Assuming 1.5 percent growth in traffic volumes, the theoretical benefit to offset the cost is $982 per year per for each vehicle crossing the Auckland Harbour Bridge in the southern direction (using a 6% discount rate and 30 year appraisal period). This is equivalent to 3.2 percent of the average land value in the northern area of the city.

It is worth reiterating that this is only the cost for the 800m view motorists have around the Orewa onramp. A second policy (Viewshaft E16) protects a very similar view from the Harbour Bridge, which should be thought of separately.

$1.4bn is just the beginning

- The cost of E10 (and viewshaft policy more generally) on the city centre is almost certainly much greater than $1.4bn. We use a number of conservative assumptions in the analysis:We include only costs to the city centre. Approximately 52% of the land under E10 falls outside of the city centre boundaries; these costs are not included.

- We do not include positive externalities of intensification, such as agglomeration and other wider economic benefits, which are regularly included in infrastructure evaluations. These benefits can be substantial. For instance, in the City Rail Link business case, agglomeration benefits were roughly 37% of conventional benefits.

- We only include private land – but public land could also benefit.

- We use 2014 land values. Since the cost of the policy is driven by demand to locate in the city centre and growth has accelerated in recent years, the cost has likely increased since 2014.

- We estimate only the cost of E10. The city centre is further constrained by E16 and the Museum viewshaft. In total, around half of all private land is constrained by viewshaft policy in the city centre.

So are motorists prepare to pay $982 per year?

The short answer is we don’t know. But we can give some context to the number. The average, after-tax household income in Auckland is $66,000. After we deduct mortgage payments on the median house price ($855,000) and transport costs, a disposable income might be around $10,000. This is useful to benchmark the cost, which is around 10% of annual disposable income. A not insignificant number.

A win-win

For those that remain unconvinced, we take the analysis one step further. Let’s say you believe that motorists are willing to pay more than $982 per year. Is there a way that we can protect the view for motorists and reduce the costs? Yes.

The current design of E10 requires motorists to look over their left shoulder to see Mount Eden. Motorists are driving perpendicular to the viewshaft – a remarkably inefficient design for the city. To demonstrate why, we rotate the viewshaft 4.5 degrees to the left, so that E10 intersects with a southern turn in the motorway (Figure 6). Motorists now drive ‘into’ the viewshaft, so its width over the CBD is reduced. This maintains the view for a similar amount of time, avoids Onewa Rd onramp (which obstructs E10) and is probably safer for motorists (they can look ahead at the view rather than to one side). The benefit to southbound motorists is largely unchanged and the city saves 43% of the cost.

Viewshaft E10 has become a significant roadblock to Auckland’s own ambition. The city has options. It’s time to start looking at them.

Processing...

Processing...

Great article Geoff. I think the first step, for most Aucklanders, is just finding out that the viewshafts exist. Only once there’s more awareness can there be an informed public conversation about this.

I personally think that we should just get rid of them all. This is a policy that’s preventing the development of more housing in areas that are ideal for densification. While we still have people living in cars, we can’t afford to have policies that prevent development for no measurable benefit.

+1

100%

Great analysis. Looks like a complete no-brainer. The question is – how easy or difficult is it to change the viewshafts?

We should abolish all viewshafts from roads. Museum to Mt Eden is at least somewhat sensible: Pakuranga Highway to Mt Wellington is not.

absolutely. There can be no justification for claiming a ‘benefit’ that accrues only to passengers in vehicles, and to drivers who aren’t paying sufficient attention to the road ahead of them.

At least the Mt Eden viewshaft actually works. I mean rightly or wrongly you can still see Mt Eden. The Auckland War Memorial Museum viewshaft D19 stops development so you can see to and from the museum. But the trees have long since grown to block most of the view so it is costing people development and there is no view. https://www.google.co.nz/maps/@-36.8601172,174.7778524,3a,75y,24.98h,90.73t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sbrKC1Zk8Pd8A2l37sk9aeQ!2e0!7i13312!8i6656

Once all those conservative assumptions get costed as well, the $982 could easily rise to $2500 or more… that’s a quarter of each motorist’s disposable income. Of course motorists wouldn’t be interested in paying this. Yet I guess they are, in commute time – many of them could be living in those view shafts, or in closer homes vacated by people who do.

Great analysis, thanks. I agree with SB that some view shafts may have merit, but these motorists’ ones do not. Would we be ensuring that all modes have equal views, next?

Why do assume that only motorists enjoy the view. How about those sitting on the bus; must they shield their eyes so that they do not enjoy that same view?

True, and once we have sky path, that’ll be a few more. Indeed, I wonder how much we can factor in the emotional benefits the view provides to people on an otherwise dreary commute.

then draw the viewshaft from the top of the bridge. People in buses or being passengers in cars can then appreciate a panoramic view of the city and Mount Eden behind it, from an altitude that doesn’t block development to sensible heights.

Very interesting article. Is rotating the view shaft as proposed possible still physically (ie. are the existing buildings low enough)? I’d imagine this would kick up a humongous fuss with the land owners now affected anyway so probably better that it is dropped.

If Onewa interchange obscured some of the view shaft does that comply with the policy, or is it just outside of it?

So if one deletes the viewshaft, >$1bn of windfall benefit accrues. But to whom?

Existing property owners, as they now have more possibilities for land usage.

And the council because the rates would increase as well.

I guess if there’s a case for removing the view shaft, a clever government or council would buy property there, remove the view shaft, and develop, so that the general public could gain more from the benefits.

It is an indirect flow.

There is some social benefit that will flow to people due to intensification.

Examples of that includes:

-High density means more dwellings for people to live closer to city

-Encourage more PT uses due to high density

-Improves local amenity due to more residences and local economy

-Improves walk-ability due to more compact city

-Encourage urban rejuvenation – demolish the old low raise rundown warehouses and replace with fancy high rise buildings

-Encourage capital investment due to the improved feasibility of redevelopment

-The inflow of money also creates jobs, and new business opportunities

The 1.4b benefit is underestimated

Yes, and all that can happen without a select group making the biggest windfall.

The apartments on Hobson Ridge fit under the view shaft and they’re on top of a hill. So it’s most certainly not limiting that area to warehouses. Probably a more limiting factor is the state of the street grid in the area. Having roads like Cook Street or Nelson Street in front of your proposed apartment will limit how appealing it is. It takes away many of the advantages of inner city living.

This is much more applicable to the nearby heritage overlay. Only a few kilometre away, so only a short ride on a simple push bike to the city. Or alternatively a short bus ride. (that bus ride is now often not there due to that low density).

You can also look at that overlay in the same way as looking at the motorway junction. It creates severance. Any high density development further out will now be separated from the CBD by a few kilometres, making cheap ways of getting around (walking and plain old bicycle) less viable, and PT lines longer and more spread out.

The severance created by the residential parking zones will become more and more apparent, too, in those heritage areas. Grey Lynn’s getting one next February.

That public space should be for all to use, whether priced parking, placemaking with trees and footpaths, sustainability mobility (better pedestrian amenity, cycling infrastructure, bus lanes.)

Instead AT has tied it up in a way that reinforces a non-existing right of the residents.

Wrong. Rates would increase for those properties, but total rates take would remain the same. Council gets very little benefit. Wealthy land owners would get huge tax free capital gains, courtesy of the rate payers of Auckland.

It does sound like a proposal to more or less privatise something which is currently more or less public (the space above the buildings in that area), with the benefits accruing to the existing landowners, who no doubt bought the land with awareness of the limitations.

The ‘indirect flow’ of benefits Kelvin lists seems very indirect…trickle down economics? I say if you take something from the public, you have to give something back (directly, not indirectly).

What is the actual limit in terms of the numbers of stories that buildings may currently rise to in the study area? We should remember that many cities are quite dense and have the suggested benefits, without shade-making, wind-funnelling towers. It would be good to define what the actual limits are. We might like six-to-eight storey buildings more than thirty-to-forty.

Not quite wrong. That area is subject to the city centre targeted rate, which is a direct rate against property value (not a proportion), and does increase if the value goes up.

And given that the actual public benefits are quite low (random unsafe view of a volcano for a few seconds on a motorway that hardly anyone even knows exists), then you really aren’t taking away much value from the public, so it wouldn’t take much return from agglomeration benefits, etc, to make up for it.

Isn’t this a good case for a value capture system like have been suggested for new PT corridors? I don’t have a problem with the land owners getting some capital gains out of this but the bulk of them should go to the city.

People who need a place to live or work?

Could implement a targeted rate on affected properties based on the increased valuation/zoning change although if the value increases then so too will their rates.

The alternative viewshaft appears to align remarkably well with a possible second harbour crossing. Perhaps that’s how it should align? If the second crossing were a bridge for light rail, with walking and cycling, that would be a spectacular view. It would also be seen for rather longer than the few seconds it takes to drive the couple of hundred metres on the motorway. In any event, viewshaft E10 is no doubt a consideration for any possible bridge. For that matter, the oblique end-on view of an arched structure could well enhance the view.

It’s unclear how the policy would benefit motorists along a new bridge. The viewshaft tracks upward from the motorway, so a new bridge could easily miss the view – because it would fall below the viewshaft. If a tunnel is preferred to a new bridge though – which is very possible – then AM peak traffic on the existing bridge is projected to fall by 15-35%. So you can expect the required willingness to pay (roughly 1k) for Viewshaft E10 to go up by a similar amount.

Looking at new architecturally designed landmark building is also attractive.

But not unique. Auckland’s cones are pretty special. So are Auckland’s people, of course, and shouldn’t be sleeping in garages.

Exactly! When approaching the bridge what you actually admire is the city. This is hilarious, it’s like arguing that Manhattan is in the way of the view from Brooklyn of New Jersey….

Really interesting article. I always understood the viewshafts as public property. Protected public views OF public spaces FROM public spaces. That public property now has some value which shouldn’t be privatised.

While I live much further south, I think for Auckland it is a very unique aspect of the city that should be protected.

I’m not Maori, but I suppose all the cones have some important cultural links to some maori tribe somewhere. And as part of honoring the ToW I think this is a small part of that.

I mean, if you argue to remove viewshafts, then you may as well remove all height limits everywhere, that no one is entitled to a view and you neighbour can build a giant wall to block any view. I don’t have a problem with that as long as it is consistently applied, not just avoided by rich lawyer folk who can challenge it.

You could argue we could just turn all the cones into quarries and flatten them to build more houses.

At what point do you reach a balance between quality of life and making room for more immigrants and growing families?

I tend to agree: if we’re going to have regulations that limit development and force up the cost of housing, then viewshafts are probably some of the better ones. They’re protecting one of the unique and culturally significant things about Auckland. I can’t see the same rationale for protecting villas, for example.

That’s not to say that all the viewshafts are equally important or deserving of protection, though, and in this article Geoff has used a case study of one which seems to be less deserving.

“At what point do you reach a balance between quality of life and making room for more immigrants and growing families?”

It’s a matter of balance & I think the balance should shift a little away from too much of this viewshaft protection. Certainly the road view ones.

Any viewshaft based around motorists should be dismissed on safety grounds – if you’re driving, you shouldn’t be sightseeing.

Interesting article though, look forward to a continuation of the series.

Curious that NZTA have very strict rules regarding advertising and other visiually distracting objects nest the motorway, but Auckland Council have a rule designed to let motorists stare wistfully into the distance. Go figure.

Good work Geoff and Kabira!

A good conversation for auckland to have, and data like this will certain sharpen minds.

However, an important consideration will also be the cultural value of the maunga to mana whenua, especially with *some* of the viewshafts potentially forming an important part of a protection and management regime in any future World Heritage site bid. Many of the viewshafts probably reflect longstanding cultural connections, with the landscaping being visible signs of the cultural imprint of different mana whenua tribes on the land. In addition, many of the maunga have cultural interconnection which is reflected in the intervisibility between them. obviously E10, the subject of the analysis, probably doesn’t come into this category.

Anyway the point is that it isn’t just an economic conversation, but in the post-Treaty-Settlement world of Auckland it is also fundamentally a cultural conversation. And not in the sentimental pakeha sense either that usually sees opposition to considering getting rid of viewshafts (which is probably reflective of trying to protect property values as much as any real care for heritage). Mana whenua as owners of the maunga would need to direct this part of the conversation.

It is clear now that the various Auckland councils as well as various Central Governments have failed Auckland. We need to deregulate and allow people make their own choices about what they do with their land. The viewshaft for a motorway is plainly ridiculous but I am sure there are many others as well – let alone so called “Character Overlays”. Until this changes we will have kids living in cars – that’s not a hyperbole.

But at least the homeless can see the local mountain I guess…

And how many homeless are Maori? Cultural rights to a nice view being more important than the right to a decent whare seems like a society whose cultural priorities are messed up.

Brendon Harre – that’s a cheap shot. You can’t really be suggesting that a homeless person could realistically buy or rent a home in the E10 zone if the viewshaft was removed.

More homes = more homes.

Why not, the apartments immediately adjacent to or under the E10 viewshaft are among the cheapest homes in Auckland. Some of the small studios are as cheap as one third the Auckland average. Indeed many are owned and operated by Housing New Zealand.

More of those would do wonders for housing supply at the bottom end of the market.

The Character Overlays is another ridiculous policy that often abused by nimby to stop any development.

Council are protecting views, (not very) old houses and parking while also telling people how they must build their house, how big their back yard must be, where their living room must be located, etc. One wonders why we have a housing crisis…

I find it really odd they choose to reference some unknown source about the reference point of E10 being the motorway. It’s like they are stating as fact that the view shaft was about giving a view to a motorway. Where is the evidence???

I think it should be considered in reverse as well. What about views from the top of Mt Eden to the harbour? A public view of the harbour bridge and part of the harbour from MT Eden, worth $1.5B. Isn’t that worth protecting? Instead of a view of a bunch of dreary office towers and apartment blocks? Once it is gone, it is gone forever. Widen or shift the view shaft as suggested, but go further to include the view of the Harbour Bridge.

Hi Ari. We reference planning documents in the paper which detail the reasons for protecting the view for motorists. I’ve never heard anyone make a case for protecting a view of the motorway for people on Mount Eden. Your point about seeing the Harbor bridge from Mount Eden is a good one though. But Viewshaft E10 does not protect that view – Viewshaft E16 does this – so it is not part of our evaluation.

But shaft E10 does protect views of **the harbour** its water, layout and such from Mt Eden, including but not limited to the “motorway” and the adjacent wetlands on the north shore and along the harbour edge where the motorway goes – where the viewpoint comes from.

You say E10’s origin is a Motorway, I recall its actual origin is stated as from the area at/near the motorway corridor, but its near or at the intersection of Barrys Point Road.

Yes its not a nice piece of town, and now has a lot of lanes of motorway traffic, it had a lot fewer when it was designated back in the day. And Barrys Point road was not such a traffic sewer.

All such viewshafts originate, by design from public places – which means that usually road corridors and not private land are at the “point” of the viewshaft. Viewshafts are public property in that way.

So the obvious conclusion is that “motorists” are the prime target is erroneous when in fact thats a planning convenience/simple designation technique to be able to easily designate public land as the origin. not least as council has full control of the public spaces/corridors and can designate easily their lands, whereas the same for private land is not so easy.

Yes motorists gain a “free view”, but the same can be said for motorists driving both ways along Tamaki Drive. [or coming north on the Southern Motorway] – They too also gain wide sweeping views “for free”.

Its really part of the “cost” of protecting the visual environment.

Ari, viewshaft E10 is literally defined in the statutory plan as being from the motorway to Mt Eden: See the Unitary Plan entry here: http://unitaryplan.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/Images/Auckland%20Unitary%20Plan%20Operative/Chapter%20M%20Appendices/Appendix%2020%20Volcanic%20Viewshafts%20and%20Height%20Sensitive%20Areas%20-%20Values%20Assessments.pdf

Thanks Nick. I understand the origin point in the current plan, but I was meaning more about the original intentions from the 1970s. Is that in the plan from the 70s? That the view was for people using the motorway? I suppose that was the way things were like back then. Protecting views for people driving around Auckland.

It was in an era when families would go for “Sunday Drives”, so it’s not so surprising, I guess.

Is Wynyard quarter actually built up all the way up to that view shaft? I don’t think the buildings over there are even remotely high enough to block any views. A bit further we have 13 storey apartment buildings on top of a ridge.

I’m also curious what the result would be of a similar analysis of the ‘heritage’ zones nearby.

Wynyard Quarter is a design decision to build low raise business park style buildings.

The hypothesis is medium density is healthier.

This may applies to state houses residential.

However for office and business, low raise lacked vibrancy and amenities. The whole place become ghost town after work.

Also it is harder to provide decent PT to low medium density compare to high density.

If we build it high density, we could have Queen St night life, shopping and entertainments.

Perhaps the dumbest viewshaft of all was the one protecting the view to Dilworth Terrace Houses. It restricted development on the old rail yards area so that people could stand on quay St and see these old houses on the cliff in Parnell. The real purpose of it was actually to protect the view of a Court of Appeal Judge who lived in one of them.

Why don’t they just stop anyone building anything and protect all views? If they had enacted that 150 years ago Auckland would have great views (actually probably not there would be trees everywhere).

How much 4-storey development is prevented in the viewshaft?

For this one specifically: given that there’s currently 13-storey apartments under that viewshaft, and given that there are already 4 storey buildings on Wynyard Quarter, probably none.

Our efforts would probably be better spent on lifting the protections on the Private Heritage Museum to allow 4-6 storey development there…

Completely agree, where a Villa is of special Heritage interest then sure protect it but pretty much blanket bans on intensive development within huge areas of Inner City suburbs is just absurd and purely exists because we in NZ fear we have no architectural history like the rest of the World does.

Honestly, whilst it might unlock some development and whilst it may have changed planning rules that possibly could have stopped the squat L-Shape ‘slums’ on Hobson and Nelson, I don’t think there would be too much change had the view shaft not existed.

If we struggle to build 4 or 5 levels on main atereral routes like Dominion Road then I think we’d struggle to see 30+ level towers on the western side of the CDB.

I agree they should be removed. I think it’s a nice idea being able to see Auckland’s natural terrain, but I personally enjoy seeing Auckland’s built environment much more, and any protected view from a motorway is insane for many reasons,

As the only thing you should see when driving on a motorway is the road and direction sign’s anything else is a distraction.

And motorways are a common sight in Auckland, especially along our shore lines, and we don’t even try to hide them or make them attractive,

Like the Waterview interchange, much of that should of gone under sh16, and should I mention the harbour bridge.

The best way to see Auckland’s volcanic cone’s is from the hills themselves,

So maybe just prevent tall structures from being built to close to the hills to prevent views from being blocked.

The shafts protect the area from uniform ever higher buildings and the associated street level canyons and wind tunnels. They beak up the developement opportunities and are a known for the property owners.

Why change for the sake of money but consider the aesthetic of a city that is not uniformly developing skyward with denizens running around at ground level.

So you’d say the squat L-Shape wall to wall apartments along Hobson and Nelson are aesthetically pleasing? They are built that way because of these viewshafts, trying to cram as many apartments into a squat building with no podium or setbacks? Have you walked along those streets? A view for driving vs a view to live among!

This report looks at just that issue and a lot of other things related to building height in Auckland:

https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/unitary-plan/history-unitary-plan/documentssection32reportproposedaup/appendix-3-6-4.pdf

This analysis points out exactly what is wrong with the application of the RMA.

There is simply no positive socioeconomic cost benefit justifying the view-shaft rule.

All planners should be forced through RMA amendment to undertake such economic/social/environmental analysis individually for every single rule they wish to include in any RMA planning document. (the current overall S42 analysis in comparison is a joke).

The mere fact that substantial analysis is required for every rule will limit the implementation of new rules to those that are necessary, and not the pages and pages currently produced.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/waikato-times/opinion/107308006/hamilton-planning-has-got-out-of-hand

The RMA amendment should also require existing rules to be retrospectively analysed – those failing to provide net economic/social/environmental benefits should lapse.

There’s a fair bit of concern regarding landowners profiting immensely from removing the viewshaft which is understandable. However as council effectively own the air rights for each affected property then couldn’t these be sold at a market rate? It could potentially net the council hundreds of millions for little if any loss in amenity.

The viewshaft rule is often no more restrictive, or not much more restrictive, than the underlying zoning rules. Was that considered in this study? (Ie. the zone rules have as much to do with development rights and property values as the viewshaft rule)

And the viewshaft does not necessarily dictate the zoning rules. The cbd has a long planning philosophy of density disappating as you move further out from Queen Street.

Hi Matt. This is a pivotal component of the analysis. The evaluation shows clearly that E10 is the binding regulatory constraint. There are many viewshafts where this is not the case (I would guess a majority) – but not in the CBD. As you say, development does dissipate as you move out of the city centre – which is what Figure 4 shows. But the viewshaft means it dissipates much more quickly than it otherwise would (in the order of 40%).

thanks Geoff. How did you measure the development impact of the viewshaft height rules?

Presumably you looked at the viewshaft height limit less the height limit of the underlying zoning? Which would then provide a height differential which you would convert into floor area differential?

We evaluate all land on either side of E10. Land under E10 is constrained, land outside E10 is unconstrained. We control for other differences in land (heritage, distance to the CBD centre, elevation etc) – until we get a smooth line (not quite horizontal, but with equal gradients), for land values moving away from the CBD. We make sure no other differences exist. This then allows us to construct an average for land values per square meter, outside and inside the viewshaft, controlling for other effects. The difference in land values is then attributable to the policy – because there is nothing else that can explain the difference. The regression discontinuity design means we don’t need specific estimates of floor space supply. It’s a demand analysis and therefore isolates the causal impact of the policy. It is not based on hypothetical supply or capacity estimates.

As commented above, car and bus pax can enjoy the view. The view of Mt. Eden gives an iconic backdrop to the city which would be destroyed by removing the view shafts. Another view shaft protects the views of the Museum and Mt. Eden also over the Parnell commercial area. The Museum with it’s Greek columns looks spectacular on its hill in the domain. Reminds me of Athens and the Parthenon above, especially from the Devonport or Waiheke ferries And I imagine from cruise ships. Leave the view shafts in place but allow unlimited height in the core CBD, Manukau CBD and Takapuna CBD .

The problem is the viewshaft lies over half of the core CBD, which already has unlimited height otherwise. That’s the whole point of this analysis!

I’ve driven over and been a passenger when driving over the bridge hundreds of times and had never realised there was a view of Mt Eden until this discussion began.

One thing I have noticed driving along here is the best city skyline and harbour view you will find anywhere in NZ.

Yes I’m mainly always looking at the cityscape along the waterfront, didn’t realise either. It is a good point raised, though, somewhere in here that the viewshaft applies the other way around from the mountain top too.

The only view shafts should be from other Volcanic Cones i.e ensure you can see Mt Eden from Mt Victoria or Mt Hobson…this essentially means low rise near and around the Volcanic Cones. I’m not sure they had Maoridom and Cultural meaning in mind when creating a view shaft for drivers paying from a toll booth. Eliminating a view shaft doesn’t mean its no longer visible and nobody is arguing blocking its view, but to limit half your already constrained CBD’s growth when growth is predicted to continue is a bit crazy.

Deliberate misstatements on RadioNZ Nine to Noon today:

“You have to look over your left shoulder to see Mt Eden” WRONG: You look slightly left of straight ahead. The designated viewshaft retains views for lots of people/properties outside the designated source of the viewshaft. They are willing and able to swivel their heads if necessary.

“These properties are totally constrained by this policy” WRONG: They are partially restrained by this policy and also restrained by many other policies.

“People want to live in Auckland and this policy is preventing them” WRONG: There are lots of development opportunities outside these viewshafts. Developers haven’t stopped work.New apartments are being built.

The Wynyard area and others within the e10 viewshaft are building to 5 or 6 stories. Developers might otherwise be able to build to 25 stories but we don’t want that everywhere in Auckland.

If not in the city centre, then where exactly would you want 25 stories?

We don’t need 25 stories in Auckland. Go a kilometre to the west, and you’re in an area with a population density of under 4000 / km². Which in the context of a city of over a million is almost zero.

Advocating for more density under that viewshaft means we have reserved most of the inner areas for the rich, and the rest has to crowd together on the leftover areas between those motorway ramps.

Completely agree with the sentiment around the inner suburbs, its a joke and should be addressed, however in NZ we deem high rise CBD apartments something for the less wealthy and for students.

In most developed Cities, the Central City normally has the most in demand luxury high rise apartments and the CBD is alive 24×7 with the best restaurants and cafes that never close.In Auckland this tends to be the opposite due to Nelson St, Hobson being pretty much motorways, if you make a livable CBD, people will WANT to live there.

The question is how to wrest control of Hobson and Nelson from NZTA, and put them on serious diets. This is the ‘paring down’ that Buchanan thought might happen once the councillors read the analysis of how bad their plans were.

The damage done to those roads was done despite the best advice at the time. To continue to keep them as motorway infrastructure through the densest residential area – and important CBD of our biggest city too – is inexcusable.

“People want to live in Auckland and this policy is preventing them” WRONG: There are lots of development opportunities outside these viewshafts. Developers haven’t stopped work.New apartments are being built.

Oh cool, you’ve just solved Auckland’s housing crisis with that sentence. There ARE enough properties, people just aren’t looking hard enough.

You’ll probably be saying people just can’t afford the deposits because they are too busy buying Avocados next..

You have conflated one wrong statement with other separate issues.

The housing crisis isn’t caused by the view shafts and wouldn’t be solved by changing them.

Who commissioned and paid for Geoff Cooper to research and write this report, and why?

It’s an interesting report (raising interesting questions) but I’m also interested to know what/who triggered it.

I find the discussion of viewshafts and getting rid of them UNBELIEVABLE! We are spectators at the uglification of this city for greed. You would have to be blind not to enjoy the view of Mt Eden as you come over the Harbour bridge. The volcanic cones are the compass of our lives since birth! The magnificent views of the sea are viewshafts we need to protect also, as this city is the city of sails and the blue of the harbour is the other defining quality of our lives. We definitely need greater viewshaft definition and protection for generations to come. Few people realise how many existing viewshafts were slashed under the Unitary Plan until high rise buildings block those views. As we build more crammed houses with small (cheaper) windows and dark interiors our vision is changing to close up and screen dominated so the only thing to to widen our myopic view of the world are the greater views mentioned above. Keep the viewshfts and create some more significant ones which need protection such as the views entering Howick and from Stockade Hill the historic hill in Howick.

No viewshafts were altered in the Unitary Plan.

I agree some viewshafts are valuable and should be kept, however we have so many the result is bland and undifferentiated, my opinion is that fewer more carefully selected views would actually create a greater aesthetic effect of the Maunga.

The idea of protecting important views came from London, where they are much more precise and therefore dramatic. The subject of the view hidden then revealed creating a greater effect.

Good discussion to have, but agree it isn’t simply an economic argument, there are important aesthetic values at play too.