Last week, I took a look at the question of whether Auckland is too big. (Answer: Probably not.) However, there’s also another, related question that I didn’t discuss: Are other New Zealand towns and cities too small?

“Too small” is obviously a subjective concept – what’s just right for one person will be painful for another. So I’m going to return, briefly, to the theoretical model I discussed in the last post, which analysed city size as an interplay between agglomeration economies and congestion/crowding costs.

Most New Zealand towns and cities are not large enough to be congested or crowded in any meaningful way. They are more likely to face challenges with the sustainability of local businesses and the affordability of maintaining infrastructure. Even a reasonably-sized growing city like Hamilton has experienced struggles in this area. Fortunately, it seems to be improving, but it could still do with more customers within walking distance and more people starting up businesses

But it’s not just about the number of people – productivity also matters. When businesses are more productive, they tend to pay higher wages, which increases demand for local goods and services and strengthens the local tax base. This also makes it easier to address the challenges faced by many regional towns and cities.

Unfortunately, New Zealand has a lot of issues with poor productivity, and, as Motu Institute economist Dave Maré has shown, these issues are worse in smaller towns and cities even after controlling for differences in firm and worker characteristics:

Population growth in smaller towns and cities can enhance their productivity performance, if it’s managed well. Agglomeration economies also apply in smaller places. For instance, a town with a large enough population to sustain three restaurants rather than two will also tend to have better restaurants, as increased competition forces them to raise their game.

However, towns and cities also trade with each other. A factory in Hamilton may buy parts from an importer in Tauranga. A family living in Dunedin might take a day-trip to Oamaru to check out their steampunk society. And so on and so forth. When this happens, it expands the market available to firms in each location, giving them more opportunities to benefit from agglomeration economies.

In other words, good transport links between towns and cities can enable increased productivity (and in doing so, make them more desirable for new residents and businesses). There is some evidence that this process isn’t occurring in New Zealand towns and cities. In a new research paper from the Productivity Commission, economist Guanyu Zheng investigates “geographic proximity and productivity convergence across New Zealand firms“. It offers some important insights on what’s happening at the ground level of the NZ economy.

Zheng’s key conclusion is that:

The speed of convergence to the local frontier is greater than the speed of convergence to the national frontier. This indicates that geographic proximity is important in the diffusion of technology. One possible reason is that much information and technical know-how is tacit and non-codifiable. Geographic proximity facilitates information exchange between firms and enhances the capability of firms to absorb tacit technology.

Shorn of the economese, this means that firms in Wellington tend to compete with (and catch up with) other firms in Wellington, and firms in Nelson tend to compete with other firms in Nelson. There’s less competition and catch-up between firms in different cities, which impedes New Zealand’s productivity performance. However, there are a few industries, like agriculture and professional services, where convergence happens more rapidly. These industries differ in a lot of ways, but they are both relatively knowledge-intensive, with high returns for adopting new ideas, with outputs that are relatively easy to trade across distance.

What can we do to address this?

The first step is correctly diagnosing the cause of the problem. Aside from New Zealand’s long and hilly geography, the main reason that it’s so difficult to trade between cities in NZ is the perverse legacy of the 1930s-1980s approach to industrial and transport planning. As I’ve written before, this had two main components:

- First, there was a deliberate policy of making freight transport between regions costly and difficult. The Transport Licensing Act 1931 banned trucks from moving goods more than 150 kilometres until its repeal in 1982, while the Railways Department had all sorts of obscure rules about train loading and unloading to guarantee employment in rural depots.

- Second, industry location was regulated and subsidised to ensure a stable and “equitable” distribution of economic activities throughout the country. For instance, there were regulations that virtually prohibited the opening or closing of meatworks and other rural processing plants between the 1930s and 1980s.

These policies appear to have a long-lasting negative legacy. Firms that were required to locate in small towns, paying high transport costs to sell to the rest of New Zealand, have been at a disadvantage since then. They don’t have scale in their local market, and it’s excessively costly to ship freight to the rest of NZ. As a result, they’ve struggled to stay alive, let alone to grow.

Overcoming high costs to distance within New Zealand could potentially have large economic benefits by enabling faster productivity convergence between local towns and cities as well as between them. The problem is that there is no single “Think Big-esque” thing that we can do in order to sort these problems out.

Viewed from a certain angle, the Roads of National Significance were an attempt to reduce high costs to distance between regions. They’re likely to be successful in some cases – for instance, the Waikato Expressway will make travel between Auckland and the Waikato considerably faster, and boost the Waikato in the process. However, as a strategy for addressing a system-wide issue they are likely to fall short for two reasons:

- First, too much money has been spent on urban and urban fringe motorways that will have minimal impact on inter-regional connectivity. Puhoi to Warkworth and Transmission Gully motorways are prime examples.

- Second, they leave a whole bunch of other problems unsolved. For every kilometre of RONS, there are probably twenty kilometres of roads with dangerous curves, a lack of passing lanes, or other issues. And there are also opportunities to improve the speed and reliability of the freight rail network.

In other words, we can’t rely upon the RONS to sort out our problems with geography. In some locations, they may contribute to the solution, but in others they may crowd it out.

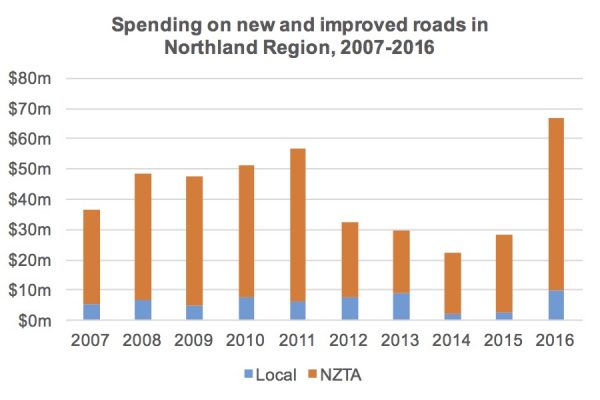

By way of illustration, the following chart shows the last decade’s worth of spending on new and improved roads in the Northland Region. This is an area where better internal road links could be quite beneficial, as travel speeds are slow. Between 2007 and 2016 a total of around $420 million was spent within the region. This is only around half of the cost of the Puhoi to Warkworth motorway, which means that you could cancel that, double funding on road links within Northland, and still have money to spare.

So, returning to the question that I started the post with: New Zealand’s towns and cities could benefit from more agglomeration and higher productivity levels. Population growth would help, in many places, but an equally important priority is to improve connectivity between towns and cities to enable more competition between places.

What do you think about the cost of distance within New Zealand?

Processing...

Processing...

The Waikato expressway is certainly improving travel times in the Waikato, but between AKL-HAM, the problem is in AKL, and this cannot be solved with more bigger roads (see ATAP). And the faster highway towards AKL incentivises more traffic IN Auckland, thereby slowing the overall journey between the centres because of congestion, and all others too. Ex-urban motorway super sizing and duplicating will absolutely funnel more movements to the big urban centre, but also more business to gravitate there.

Perhaps ironically but the peri-urban RoNS sold as regional investment almost certainly have a bigger centralising effect: You are absolutely right that Northland would gain a much greater benefit from a similar sum being spent on Northland roads, within Northland, than it all going on one duplicated highway that simply attracts more of the Auckland countryside into its urban orbit (and generates even more urban traffic congestion).

Yeah, that’s a good point: An improved road between Auckland and Whangarei may simply suck some businesses south. But improved roads within Northland will give Whangarei a hinterland.

“…First, there was a deliberate policy of making freight transport between regions costly and difficult…”

If you actually think about it for even a second, how could this statement be true? Were our forebears stupid? why would they try and make freight movement expensive in an export orientated economy? The answer is they were not and they didn’t. The purpose of the 1930 act was to rationalise transport and do away with what was regarded as wasteful and inefficent duplication of services and to ensure there were integrated timetables and services to all parts of the country. Although rail was feeling competition from road as early as the mid-1920 from trucking (not to the mention the state of the roads – many state highways remained unsealed into the 1970s) trucks were not suitable to long distance transportation. hence, any system designed in NZ in 1930 that aimed to deliver freight as efficiently as possible to as many places as possible would always seek to use rail for long distance and road for local distribution. it was not “…a deliberate policy of making freight transport between regions costly and difficult…” – it was the exact opposite, it was a policy designed to make transport, as a sinew of the productive economy, as efficient and ubiquitous as possible. The other thing to consider is NZ in the 1920s was a country struggling with it’s balance of payments post the Great War. Trains ran on locally produced coal, whereas trucks required expensive imported petrol. The wish to not be dependent on foreign energy sources was often mentioned at the time.

Thanks for coming back and engaging with the substance of the post.

The former Railways Department had a whole bunch of work rules that made freight movements costly and inefficient. Anecdotally, it was common to stop trains in rural depots and load and reload them – not for any particularly vital reason, but to prop up jobs in those towns. It simply wasn’t a very productive freight operation. Hence why Kiwirail is moving more freight today than the Railways Department did prior to the mid-1980s, with 20% of the staff.

The Transport Licensing Act 1931 was designed to offset this by restricting competition for long-distance freight movements. Regardless of the stated rationale for this policy, it had the unintended effect of reducing goods movement within NZ.

You mention ‘trucks were not suitable to long distance transportation. hence, any system designed in NZ in 1930 that aimed to deliver freight as efficiently as possible to as many places as possible would always seek to use rail for long distance and road for local distribution’. I think that is somewhat true, but if that was the case then why would it need regulation? If it was the most efficient way of moving goods, then one would have expected it to have been the cheapest therefore customers would have chosen this method anyway without any regulation.

I suspect there were other reasons for having the regulation, protecting an inefficient rail system from competition.

No, no, no Jezza, what is cheapest is not the most efficient, and what is the most efficient is not the cheapest, it all depends on what’s counted and what’s not counted. Trucks don’t have to pay (with interest) for their permanent way (let alone the deaths, injuries and illnesses their masses and emissions cause, etc., etc.). If everything was taken into account, trains would win in overall efficiency (that’s why most countries in the world – including Saudi Arabia – are investing $trillions in modern high-speed passenger and freight railways and trains).

A recycling business in Bangladesh that dumps poisonous substances into the sea may appear to be more “efficient” (cheaper) than one in NZ, but if those poisons kills all the fish around NZ and around the world, it’s very uneconomic for us to send our recyclable material to Bangladesh to be recycled, even though the recycling charges might appear cheaper, because the economic (and social, environmental and cultural) costs of wiping-out NZ and the world’s fisheries is infinitely higher – basically it means the end of human life on earth. How efficient is that?

It wasn’t so much about trying to make transport difficult. It was more about an incompetent government that believed a planned system would be better than a competitive system. Remember this was the same United Government propped up by Labour that wanted to stimulate the economy by borrowing 7 million pounds but Ward’s eyesight was so bad he promised to borrow 70 million! After the 1930 Act we had the first Labour Govt. that was never going to bust the monopoly of the rail workers. The mystery is why didn’t the first National government fix it? Maybe the waterfront strike was enough for them.

Basically, yeah.

The main argument of this post is that we should make it *easier* to operate businesses in regional towns and cities by improving the efficiency and ease of inter-city transport. Some places will still be relatively undesirable as places to live and work, but that’s inevitable. (Even if we’re ‘picking winners’ through business relocation subsidies… you can’t subsidise *every* location!)

The key point is that it’s usually preferable to figure out how to swim with the current, faster. In this case the ‘current’ is a combination of falling international transport costs, the increasing importance of agglomeration economies and skills, and people’s preference to live in sunny, warm climates. Combine all that, and it’s easy to see how (say) Northland could be a winner if some barriers were removed.

Yes I understand your point. But I think I am too fatalistic to believe in policy magic bullets. Productivity is higher in cities because more productive jobs locate there (or at least higher paid jobs locate there). Policy fixes only work if there is a poor policy in place to start with. The Motu stuff measures what exists and assumes the rest should be like the best. Kind of like saying there would be more hair around if bald men grew as much as the hairiest. We see this nonsense all the time. Graduates earn more so everyone else should do a degree. Problem is tertiary education is a sieve that sorts not a magic transformation. In your field remember the Philips curve. The greatest New Zealand economist showed inverse correlation between unemployment and inflation. Post hoc ergo Propter hoc. (which as Josh Lyman on The West Wing translated means ” after hoc therefore something else hoc.”)

Economists have generally (although not always) gotten more careful about causality and omitted variable problems. Dave Maré in particular is quite good on this. His work on productivity goes to pretty extensive lengths to address these issues.

My personal view is that there are few opportunities to make a transformational difference to living standards (or economic productivity) in a developed country, simply because we’re closer to the technological frontier. But there are lots of margins on which we can make incremental improvements. The nice thing about incremental improvements is that if you add up lots of them, you get a big number!

The National Party was formed with the specific mission of keeping Labour out of government rather than specific reform, and they have largely stuck to that approach with the notable exception of the Bolger/Shipley government.

It’s not a competitive system though, is it. If truck operations had to pay what train operations have to pay for, they wouldn’t have a look in. Trucking firms know this, which is why they ganged-up to kill the completion of the last 60 odd kms for a rail link to Nelson (source: Voller, Lois; Rails to Nowhere; Nikau Press; 1991 – my interpretation of what is intimated in the book), for example.

Even then, competitive doesn’t mean efficient. NZ had the most efficient electricity system possible under the NZED; but since “competition” has been imposed, the costs and prices have escalated ridiculously out of proportion with anything real. E.g., what took a handful of civil servants on modest median salaries of maybe $50,000 in today’s dollars now takes hundreds of CEOs, CFOs, COOs, etc, on six- or seven-figure salaries in dozens of organisations, all with their own separate headquarters and marketing and advertising, etc. It’s totally uneconomic, but it’s called “competition” so the mantra says it must be more “efficient” – but it’s not.

“…Second, industry location was regulated and subsidised to ensure a stable and “equitable” distribution of economic activities throughout the country…”

AKA a regional development policy, something still practiced by practically every developed country in the world outside NZ, run as it is by neoliberal fanatics.

Much of the growth of Auckland and the agglomeration of economic activity in Auckland is predicated on cheap energy and the ease by which goods can be shipped from central hubs to the regions over our modern and well maintained highways. Thus, it is cheaper to, say, make bread or beer in Auckland and truck it to Taupo and Napier than it is to have seperate bakeries and breweries in Taupo and Napier fufilling local demand. If the true cost of transport (carbon offsets, cost of road rebuilding, etc) was charged it may be that corporate bakers and brewers decide it is more profitable to re-open their bakeries and breweries in the regions, especially if government subsidies were available to aid relocation. This could automatically serve to a) stop Aucklands growth by shifting jobs to the regions, b) stimulate economic activity and population growth in the regions and c) reduce carbon emissions and help the transition to a more sustainable economy.

So you want to wast the public purse forcing businesses to set up where they don’t want to be and where it is inefficient for them to locate?

There is absolutely nothing preventing bakers from setting up in Taupo… except the inefficiency of the operation, the lack of economies of scale, the small market and the long supplier chains.Do you want Taupo to have more expensive bread, or do you want a government subsidy to lower the price of Taupo-made bread to what it would be if you didn’t force the bakery to go there in the first place?

First of all, nobody is forcing anyone to go anywhere. There is no such thing as a free market, the state already sets (or doesn’t) arbitrary rules which skew the playing field one way or the other. Simply offering subsidies – say, tax and rates relief and help with the cost of relocation – to businesses to locate into areas requiring development is perfectly fine by me. Secondly, it may be the case that the “inefficiency” of operating a bakery in Taupo is at least as much a result of current government “free market” policies as it is of scale. Thus, stronger laws against anti-competitive monopoly practices like pushing bread prices down until all the locals go broke and forcing road transport comapnies to pay the true costs of of road transport and climate change mitigation may reveal a Taupo baker to be not that inefficient after all. Certainly, if there is a small difference the state may decide to subsidise the local baker and his or her 30 staff for the sake of community well being. That is how you operate an economy for all the people, rather than for the shareholders of corporate bakeries.

Sorry, replace ‘force’ with ‘bribe’ then. Whatever you want to call it, it’s the state spending public money to make companies set up where they don’t want to be.

You realize that a Taupo baker still has transport requirements for their supply chain right? If not finished bread then four and yeast as raw materials… which would be most efficient coming from a centralized distribution warehouse, probably located next door to the regional sized bakery in south Auckland.

Well, to avoid this horrible situation I suggest state-run bakeries (KiwiBuns!) thus avoiding the need to use public money to influence private companies.

Plenty of people willing to see their tax dollars used for some social services (education, health) but not for others (healthy regional cultures etc.)

I would argue it’s not a healthy region if it can on thrive by being propped up by eternal subsidy for the public purse. For a properly health region they need to be sustainable, both economically and socially. That means not trying to return to the past after things have moved on (i.e. subsidising industry to setup small inefficient operations dotted around small towns), but finding the right approach for current and future conditions.

“Whatever you want to call it, it’s the state spending public money to make companies set up where they don’t want to be.”

And if I replace the word “companies” with “roads” in that statement, that is exactly what we have now with the RoNS program do we not?

i.e. the state spending public money putting in roads that don’t actually need to be built, when they could spend a lot less money fixing up whats already there. And achieving the same, or in many cases, a better, effect.

As for your comment about the raw materials being in a bulk/distribution warehouse in Auckland.

In actual fact, with modern supply chains, and just in time deliveries, the “raw materials” for said bakery are more likely to actually be loaded into several trucks, all driving up or down SH1 to or from the regional bakery [with resulting and ignored emissions galore], than they are sitting in a bulk warehouse or flour silo.

But to come back to the original topic, Sanctuary is generally right with their comments.

By not accounting for all externalities [transport emissions is just one such, more obvious example], you do not account for the true cost of whatever policies are [or are not] enacted. And the picture becomes skewed one way as a result.

Despite what economists like to believe, Labour for one, is simply not as mobile as capital, or trucks are.

People who live in say Taupo [or Hamilton or Whangarei, Christchurch or Steampunk-land Oamaru] may not simply up sticks and move to Auckland on a drop of a hat as economists and Treasury might like.

For all sorts of reasons, including, kids attending local schools, the higher cost of housing in Auckland, access to transport or losing access to local facilities or family [e.g. free child minding by grandparents] if they move away from a given area.

So as a result the government is right now subsidising lots of people to the tune of hundreds of dollars a week via Social Welfare benefits of all kinds, to enable them to stay in these regions already. The externalities are already piling up, but are usually ignored by the accountant and treasury bean counters.

And don’t forget all those “working for families”

subsidiescredits the working poor [and not so working poor] in Auckland and elsewhere in NZ are currently receiving, yep they’re all subsidies too, just not perceived as such.After all just like one person’s “terrorist” is simply anothers “freedom fighter”.

So one persons “subsidy” is simply another persons justly due “reward”.

Its largely all in the terminology, and initial starting point of view.

So maybe what we need is a proper sort of policy accounting that takes into account a more holistic view than the narrow focus on monetary value as the prime dictator of policy as we have today.

That would be the one change I’d seek, as the resultant flow on effect of that change would automatically cause a rebalancing in policies towards a less “one size fits all, all or nothing” approach to this we get now.

Greg – if I’ve understood correctly what you are describing there is moving the allocation of resources from the market to someone’s opinion, and many people who may support this wont necessarily agree with the decisions ultimately made. We already have this with Steven Joyce and MBIE deciding they know best regarding allocation of resources and deciding to prop up Convention Centres, Aluminium Smelters and dodgy revenue sharing arrangements with American Venture capitalists. I can’t see how having more of this will in any way be better.

As a socialist I have been opposing neoliberalism for a long time, but so many of the arguments here which use “neoliberal” as a bogeyman are conservative rather than socialist arguments. Can I start with this “bread” argument which seems to assume from the outset that Auckland’s growth is a bad thing, and propping up regional centres would be a good thing. This is one of those shibboleths of what I call the “conservative left” that needs challenging.

In fact, PROMOTING urbanisation will reduce carbon emissions much more efficiently than trying to make provincial centres economically self-sufficient. For example, this is because electric public transport makes more sense in Auckland than in Taupo. I endorse promoting electric rail over trucks – I oppose promoting provincial towns (and the provincial, undiverse, majoritarian mentality they breed) over thriving cities.

Yeah, in a general sense I kind of agree with some form of bolstering other parts of the country. I think NZ needs another thriving city like Auckland. Christchurch would have got there if not for the earthquakes – I knew a few people pre-earthquake who were making the move down there at the time. I just think there’s too much pressure on Auckland with immigration, house prices, infrastructure etc. It seems like Auckland has reached its critical mass and is the only ‘city’ option for our undoubtedly attractive country.

This means we tax productive and profitable business to support inefficient businesses. I am not an economist but I can’t see how this will work for too long.

Well, the inefficient trucking industry seems to believe that they can suckle from the public purse forever, courtesy of the endless subsidies they receive from NZTA and their ilk, with RoNS and $2B+ urban motorways on tap. And they also demand a level playing field and expect a free exemption forever from paying for CO2 emissions – like our farmers also get.

Meanwhile good ol’ KiwiRail has to go cap in hand to the Government just to stay alive, and to beg for its insurance payouts on its railway assets to be spent on letting it fix up said railway assets. In the stubborn belief that rail is inefficient and trucks aren’t.

Is that “efficient” enough for ya?

Greg – I would have thought removing those effective subsidies would be the way to go rather than adding in regional subsidies on top of existing effective subsidies.

I agree that we should be properly apportioning the true costs of transport, such as road maintenance and emissions. However, if a business is still not viable once these are accounted for then I definitely don’t want to see my tax dollars subisdising regional businesses.

The other option that wasn’t considered is just let these small towns die. Towns and even cities come and go and there is no reason why any single town should exist forever. Rome at the time of Christ was over a million people but a thousand years lower got down to a low of 20,000. Maybe that will happen to Auckland. We are constantly being told that we are a migrant nation; if people want better jobs and opportunities then they should move. New Zealand only has enough people to have one small city (Auckland), a few large towns (Christchurch), some tourist places (Queenstown), and then agriculture communities (Hamilton). No point spending billions to prop these dying places.

For context, here’s a list of the urban areas in Sweden: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_urban_areas_in_Sweden_by_population

And Norway: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_urban_areas_in_Norway_by_population

And Finland: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_urban_areas_in_Finland_by_population

All three have a major commercial centre, a couple of medium-sized cities, and a long tail of small cities/large towns a la Gisborne and Timaru. NZ doesn’t stand out as having an unusual urban structure for its size.

I never said NZ was unique – the difference of course is that with a radius of 2000km these towns have 500 million people to trade with and we have ocean.

I would have thought that is largely current policy. Do you have any examples of towns we are propping up currently with tax dollars that should be left to die?

Whichever town tiwai is closest to for starters

Good point, especially given I mentioned Tiwai in one of my above comments! I don’t think Invercargill would die if Tiwai closed (which is pretty much inevitable at some point) as the rural economy is it’s main reason for existence, but it would certainly have significant impact. I cant think of any towns in NZ that would cease to exist if government support for a particular business ceased to exist.

I agree that very few would completely die as they will always be rural service economies, but if we removed the subsidy of unpriced carbon to dairy farming a lot of places would really start to struggle fast.

I actually think that NZ’s regional centres are too *large*.

Reducing Whanganui, Gisborne, and Whakatane to 10,000 people, would immensely help them. Currently they are too small to be actual cities and too large to simply serve the adjacent rural areas.

Places like Hamilton, Palmerston North, and Ashburton need rail services to the major regional hubs to increase their connectivity and make them viable.

Palmerston North does have rail services (passenger and freight) to a major regional hub, and in fact in terms of rail freight and logistics is probably more of a regional hub itself than Wellington, or well on the way to reaching that point. The regional council based in Palmy part owns the Wellington port and Palmy sends a lot of freight to that port by rail. For a city with a train station so far out of the CBD it’s a miracle that Palmy still has passenger services. Hopefully something can be done to improve this.

Thanks for that infor, wasn’t aware of the logistics going on there, it’s great to hear.

I was aware that the capital connection was still running, but was meaning *more* services for all three cities (ie more than 10 per week PN, 3 per week Ham, 0 per week Ash).

It would be ideal if the train station was where it was originally located, Main St/The Square. Right smack-bang in the middle of the commercial center.

However, where it is is only a short shuttle up Rangitikei St – about 6-7 blocks.

“Zombie Towns – places that are actually dead, but don’t know they’re dead yet.” (Shamubeel Eaqub, 2014).

Arguably, much of NZ falls into that category – certainly places like Pahiatua does – it really just exists to sell quad bikes to the local farmers, the rest is moribund. All it needs is a petrol station and one shop selling pies, the rest can go, and honestly, no one would cry. But by the same argument, you could also get rid of moist of the South Island – I mean, honestly, its just kept open for a month or two each year for the tourists to look at, isn’t it? The rest of the time people could just go home. Seriously: Reefton? Blackball? Clarence? The Caitlins? Even Gore? Really, what’s the point?

From observing my brother’s small-medium size business in Balclutha (population ~4000), I agree with Peter that a larger population would help it to be more productive. His business is in good health, with an excess of work available – his greatest struggle is the tiny pool of labour in Balclutha. For positions that require even the smallest amount of skill/experience, he has to advertise outside the region, which involves trying to convince people to uproot their lives and shift a long distance to take his job. This forces him to raise the wages he offers, but even then he struggles, as money is only one factor people consider when thinking about relocating. A larger labour pool would definitely raise his business’s productivity.

Subsidies aren’t what his business needs to improve its productivity – things that make it easier to get suitable people into the right roles is what would help. As well as a bigger population, I think better policies on immigration, employment contracts, training, relocation, and even just better dissemination of information to potential workers are things that could have an impact on regional productivity.

There are a couple of examples of businesses in the South Island that were simply too successful for the small towns they were in. Tuapeka Gold Print in Lawrence and Designline in Ashburton, they ended up having to relocate to Dunedin and Christchurch respectively to get a decent pool of employees.

But they didn’t “have” to. They had a choice.

While you are technically correct, they had to to grow their respective businesses. The point I was making is it is very hard to run big businesses in small towns.

If your goal is a big business, you probably shouldn’t be in a small town

The point is that small towns are particular cultural artefacts that have their own value above and beyond basic economic measures.

In a small town, you can have a big section, a nice house, and still be 5 minutes drive from work, for the price of a working class salary. Your kids can roam the streets to 9pm

JDELH – agree there are many good things about small towns, but those benefits you describe are all for the people that live in them, but as someone who doesn’t I don’t see why I should subsidise this lifestyle.

I wonder whether a decent train service to allow people from Gore or Dunedin to reasonably commute there would help?

Yea maybe. There used to be passenger rail but it shut down a few years ago. I know the local meatworks busses people in from Dunedin, maybe he should try and tap into that.

I doubt it, the population numbers are too small. There have been many long distance services on that line but I don’t think even in the glory days of passenger rail there was ever a commuter service.

Dunedin suburban trains ran from Mosgiel to Port Chalmers until 1982. Gore was on the intercity which was at best two trains each way a day I believe.

The railways, until deregulation, was labelled as a “common carrier” – in other words it had to carry everything that came to it. The effect was that the railways was the courier service to New Zealand, all operated through the local goods shed. When that designation was removed I remember the consternation it created through rural New Zealand, with rural shopkeepers etc wondering how their stock would arrive – don’t forget, no courier companies in those days, and the trucking companies weren’t exactly falling over themselves to pick up the ball and run with it. I remember ordering a lounge suite from Smith and Browns in Tokoroa. The only example in the shop was a shop sample which wasn’t to be sold, and my lounge suite had to come from Auckland by train, and it was damaged when it arrived.

In addition the railways was the livestock carrier of New Zealand, but done under very tight regulations, whereby the stock on the train had to be unloaded after a certain time period and rested in a stockyard before being allowed to be loaded back onto a train to continue the journey. I’m pretty sure those regulations don’t apply to the transportation of livestock by truck.

It certainly would be interesting to see how things would be different if the true cost (including all health and climate factors) of using and building/maintaining of roads was reflected in fuel tax (not so relevant as electric vehicles are used more) or a pure road pricing scheme. What would be the affects of a lower GST income tax across the board generally but “massive” road pricing “tax” policy.

Here’s my take on the issue, with numbers: http://greaterakl.wpengine.com/2016/02/12/transport-externalities-in-auckland/