Good cities should provide choices to their inhabitants. Any big (or small!) city is composed of a variety of people with various preferences, needs, and budgets. Look around you: Aucklanders are a bloody diverse bunch, and we’re getting more so as I type these words.

The Aucklanders of the future will want to get around in different ways, live in different places, and entertain themselves in different ways. In fact, this is already happening. It’s the reason for the success of the innovative mixed-use developments on the waterfront, the runaway success of Britomart and other rail upgrades, and, on the flip side, declines in vehicle kilometres travelled per capita.

At Transportblog, we recognise the importance of choice in cities, which is why we’re so enthusiastic about opportunities to invest in a better public transport network and better walking and cycling options. We believe that offering Aucklanders more travel choices at an affordable price will improve our living standards. Full stop.

What’s true in the transport market is also true in the housing market. Offering a greater range of housing choices will raise the living standards of Aucklanders, because we want to live in different types of homes. Enabling higher-density development in more areas will make some people much better off, because they want to live in dense environments, without making anyone else worse off.

Critics of intensification often fail to understand this argument. They say: “Oh, you just want to make everyone live in a tiny shoebox apartment!” In fact, the exact opposite is true. Enabling some people to choose to live in apartments or terraced houses will ensure that there is more land available for others who would prefer a lifestyle block in Dairy Flat or a quarter acre in Flat Bush.

Essentially, urban planning that enables housing choice allows for both high-density and medium-density living options and more low-density suburban living. This isn’t idle conjecture – it’s a well-established finding in urban economic theory and the empirical literature.

A few years ago a team of economists from the Reserve Bank of Australia put this idea to the test using economic modelling techniques. Their paper, entitled “Urban Structure and Housing Prices: Some Evidence from Australian Cities” (pdf), tested the impact of different urban policies. (NZIER economist Kirdan Lees has also done some similar work for New Zealand, but his initial paper (pdf) did not look at building height limits. In any case, the results are similar.)

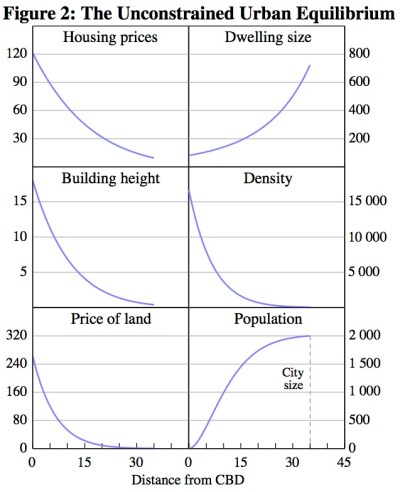

The RBA economists model a relatively simple, monocentric city with employment and amenities concentrated in the centre and the residential population radiating out in a circle – the basic workhorse model in urban economics. While this is a simplification, it can easily be generalised to a polycentric city – just imagine multiple centres rather than a single centre. Their “unconstrained equilibrium” looks like this:

In short, densities – and building heights – are highest in the areas that are most accessible to employment and amenities. Land prices are also highest in these areas. This doesn’t occur as a result of a planner’s fiat – it happens because lots of people want to live close to the action. Others, of course, would prefer to be a bit further away with more space – and that is what they get in the unconstrained urban equilibrium.

Next, the RBA economists simulated the effects of imposing a building height limit. In effect, limiting building heights would prevent people from choosing to live at high densities near employment and amenities. Here are the results – the magenta lines show the effects of the constraint:

Pay close attention to the middle two panels. They show that a building height limit does not just restrict high-density development in the centre – it also raises densities in the outskirts of the city. In short, a city that constrains medium to high density development doesn’t just fail to provide options for people who want to live in apartments. It also fails to provide options for people who want quarter acre sections or lifestyle blocks.

Has this happened in Auckland? It’s difficult to say for certain, but my research on population densities in NZ and Australian cities found that Auckland was missing out on both medium-density suburbs and low-density exurbs.

Finally, as the first panel shows, these restrictions are expected to raise the cost of housing for everybody, regardless of location or housing preference. As I said at the start, good cities provide choices for their inhabitants. Failing to provide for choice in the housing market just means that we all pay too much for homes that don’t suit our preferences.

So, what’s your dream Auckland home? Subject to budget constraints, of course…

Processing...

Processing...

I’d take the Hobsonville Point development and move it 20km closer to town.

You see this in Auckland with the high (and increasing) densities in the inner south and near west. People are infilling, and household sizes remain large. The kids might like to move out and start their own households, but they can’t afford to.

3 bed terraced house near Devonport Domain. Small garden / terrace (space for some veggies) and some storage for bikes and kayaks. On street parking for one car. I may have given this some day-dream time…

Time to get the bulldozers running up and down either side of Franklin Road. I am just not sure whether it should be four storeys or five.

No one is advocating destroying our built heritage. In fact, this blog has often pointed to the desirability of the Freeman’s and St Mary’s Bays as an example of the popularity of higher density living, and has explained out how these developments would no longer be legal due to minimum parking restrictions, setbacks and height to boundary ratios. I guess what you are trying to argue is that any multi-level development in neighbourhoods characterised by one level villa type housing would destroy its character. This does not necessarily have to be the case if these developments are sympathetically designed.

“No one is advocating destroying our built heritage.”

That was the impression that came across when the intensification debate began – some of the proponents seemed to be arguing that if the apparent wholesale city-wide intensification resulted in the destruction of existing suburbs, then the “old fossils” would just have to live with it (they would be dead soon, so who cared!). Discussion on Mission Bay springs to mind…

No you misunderstand me, I am not being sarcastic. I really do believe we would be better off getting shot of a lot of inner city villas and replacing them 4 or 5 storey buildings. Heritage is just how people used to live, not how they want to live now or in the future.

Is this Heritage Week troll/ baiting?

Completely foolish and short sighted. The UK has a $100BN a year in tourism. 24% of that is heritage tourism.

I doubt the number of tourists who travel somewhere to look at the same boxes on boxes they have back home is anywhere near that…

Why start with Franklin Rd? It’s already dense, pleasant, walkable etc. why not start with the car yards of Great North Rd, the half empty lots of a The Strand, or the completely empty land of Ian McKinnon Dr.

No need to bulldoze the quite good to build better when there is plenty of terrible to deal to first.

well said Nick

+1

An apartment in Manukau, within a low rise complex, slightly bigger than what i could afford closer to the CBD, but close enough to the amenities I require. (This is my house)

I’m sure the answers will be as varied as the readers of the blog.

Will definitely be looking through this, might even add it to our submission to the district plan down here in Christchurch, there are massive restrictions on height in all new zoning designations

The major assumption in urban economics is that people want to live as close as they can to the centre of town. In a city like Auckland the centre is only one attraction. The coast is another. Most people would prefer both if they could afford it but not everyone can afford the Herne Bay waterfront. The model will always put Mt Eden ahead of Castor Bay but that would never be my preference. Particularly since like most people I dont work in the CBD.

What “model” is putting Mt Eden ahead of Castor Bay? Other than the majority of people’s revealed preference?

(though I too, if given the choice, would probably take sea over CBD (provided ease of access to the CBD for work), but it would be a close-run thing)

The mono-centric city model referred to in the post does on the basis that Mt Eden is closer to the city centre. Price is assumed to be determined by proximity to the centre. That is the basic assumption used in the model. My point is that life is more complex than a mono-centric model, many of us choose a location based on proximity to other amenities, some of us even choose to be further from the centre in preference to closer as it allows us to have a higher quality of life with less people and a bigger house and more things for our kids to do.

But it assumes, correctly that the majority prefer to live closer and this drives higher prices there. The majority of Aucklanders if offered the exact same house 5km from Britomart or 20 would pick the one 5km away.

So you missed reading the bold text that expressly refers to those with other values, in particular for space over proximity? Try reading again.

I read that and assumed that was part of Peter’s argument. I didn’t read that to mean the Australians had modified the mono-centric model that the graphs are based on. Are you suggesting they have included other attractions into the model?

Most people don’t work in the city centre, but average commute distances still tend to be shorter for people living closer to the centre. This is because proximity to the geographic centre of the region means that you minimise travel distances to jobs everywhere in the region. (Essentially, a 10km drive gets you to more places when you’re in the middle.)

You can observe this relationship empirically with Census journey to work data as I did in a recent paper on housing and transport costs: http://greaterakl.wpengine.com/2014/07/24/location-affordability-in-new-zealand-cities-is-greenfield-growth-really-affordable/

In any case, the point of this post is not to debate whether Auckland is a monocentric or polycentric city – it’s most definitely the latter. Rather, it is to observe that policies can have unintended consequences. In this case, the unintended consequence of limiting density in accessible or high-amenity areas (wherever they happen to be) is to raise the density of other places.

Cycle ways, tracks, walking so people can exercise to work. Free pedal power financed by government. A fat takeout nation is not what we want.